Futile words and tangible events

What happens when the space for youthful aspiration caves in? When circumstances are extreme, can solace still be found in a daydream, a creative thought beyond the everyday? And what role might contemplative words have in crisis?

I would be lying if I said the war had disturbed my habits. It is tempting enough to pretend it turned a timid art researcher into a plucky military reporter overnight. But it was more likely my father’s asthma, my grandmother’s dementia, my uncle’s fading sight or even a cockroach that slipped under the radar and darkened my everyday.

Getting to grips with everything that has been happening, one should really start from scratch.

Inherited memory

Being born into a family with relatives who knew concentration camps implies repercussions. Their suffering somewhat defines your future: the special type of twitching, conversation fillers and chronic ailments you acquire from infancy on. With hindsight, my whole humble story of self-development, reaching certain conclusions (and getting rid of the others), was onerous yet predictable. Could I have avoided it, understood it in advance?

My relationship with writing started as a teenage escape from hackneyed surroundings. Ukraine’s seeming mundanity, which has soaked up more riots, upheavals, free falls and dismemberments than any other European country in the last 30 years, was abundantly poetic in a way. Yet back then I saw it as dull, vapid, unquestioned normality. Writing texts and articles became an easy way to immerse myself in more meaningfully charged environs, such as the Dionysian Mysteries, the Arabian Nights or Shakespeare’s Globe – in short, references to things I’ve never seen and the places I’ve never visited. For that very specific though poorly grounded reason, they seemed of a higher nature that mattered more, overplaying any purges, captures and hostilities that dotted my family’s past.

It was probably my father’s unintelligible mumbling that made me abandon all words rather than create scintillating writing. A 73-year-old Soviet engineer, keen on physics and maths, prone to believing that the only real knowledge is crunching numbers, grows mysteriously ignorant when it comes to his own health. When the Soviet Union collapsed, he was invited to the US, but decided to stay in his cubbyhole at an old, unheated factory, wrapping up his computer in a jacket until the factory facilities ceased to operate. He would repeatedly describe his decision as ‘virtuous’ and ‘just’; wasn’t this the precise same justification I used for staying in Ukraine? Yet the choice he made conceivably led to severe asthma. Heavy medication for such cases provokes kidney disease in the long run that can contribute towards consciousness becoming opaque. That was the exact state in which I, an up-and-coming author, found him in bed a few years ago.

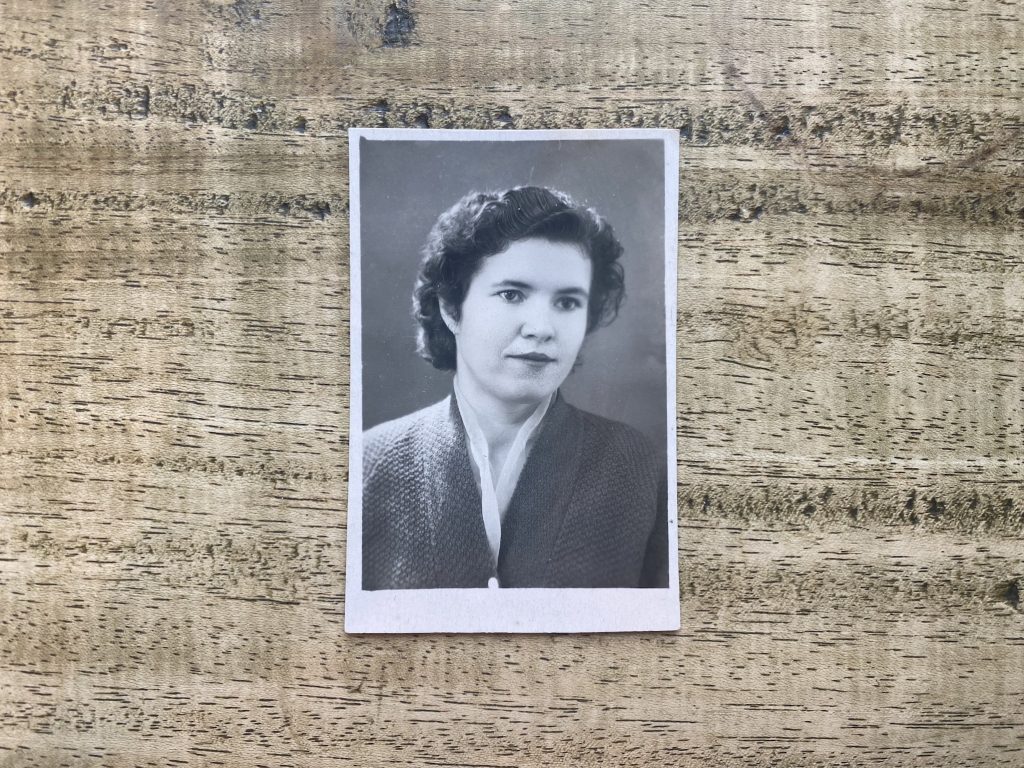

While he bore the brunt of his work habits, which were not as virtuous as they seemed, my granny was slowly dying. We managed to get her out of Nikopol, a frequently shelled Ukrainian city, almost two years before the war. After being expelled from her despondent yet precious routine, she might loiter from room to room unable to recall our names but could vividly retell the story of how a huge insect had climbed onto her mother’s face when she died in an open cargo train carriage on the way to Nazi Germany. I heard this story at least once a year when sent to granny’s cottage in the summer, but it wasn’t until I grew up that its meaning dawned on me – partly because of the childhood ability to regard all the spooky tales as late-night entertainment, partly because the harrowing memory was avidly mixed up with all the stories she would incessantly conjure such as that of her as a young curvy beauty pouring cold water from a balcony on her unfortunate admirers.

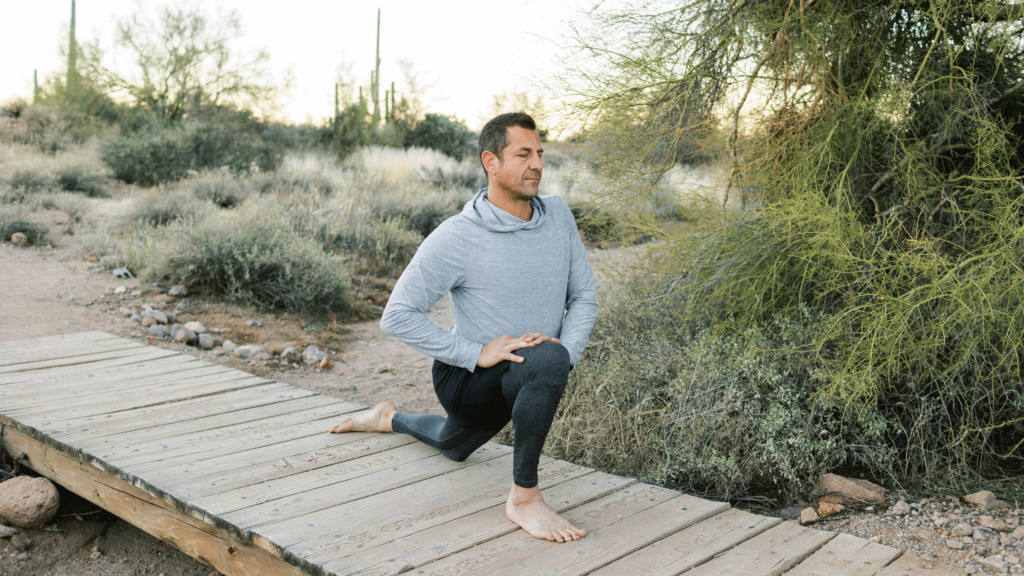

Olena Myhashko’s grandmother, 1968, Crimea. Image courtesy of the author

Needless to say, she eventually married one of those admirers; her next of kin died during WWII and she had to eat. Out of this gloomy bond came my uncle, whom she never loved, despite being the only kid who never left home. At the age of five, he was ineptly treated for Polio, giving him a limp, making him almost blind. His mother scolded him for nearly everything, who’d rather he didn’t resemble her husband as much as he did. Consequently, my uncle was dejected and grew narrow-minded. He never managed to get a girl, accompanying my granny instead in unhealthy Freudian dependence. Having joined our family house, he was basically my granny’s aidless extension with nobody to cling to himself.

The body and its parts

There are a plethora of ways in which one’s adolescence can end, and mine finished in needing to become the breadwinner. The circumstances I had once considered trite, minor and phantom smashed the door of my Soviet-like bedroom, turning my early twenties upside down; being artsy was the last thing I could think about.

When medical test results are your main reading material, you discover that facts – not previously part of your language – become all important. You quickly learn that the excrement you wash off your parent’s ankles doesn’t have any literary equivalent. Don’t attempt to uncover any hidden sense of the scene; the actual event surpasses any aestheticized retelling. The amount of new knowledge, both practical and emotional, is so huge that you start perceiving the arts as an appendage, a crutch for those who lead relatively carefree lives. The assumption that art can actually convey reality is a preposterous idea.

After all, it was probably my father’s ailment, or my granny’s dementia, or the cockroach slipping into the apartment one of those summers when things weren’t right that prevented me from becoming a writer. A ripe new world of blood, flesh, death, appearing at such an unsafe distance, also shut me up and made me feel ashamed and embarrassed, full of resentment and nostalgia for any form of writing that wasn’t aimed at helping directly.

Persistent dreams

Years later, I switched to journalism with relief. Having visited the first de-occupied towns and villages as a reporter, I was finally able to rid myself of the cowardly thinker, the detached scholar role – the last person to be rescued in a shipwreck. The desire to stand up for the abuse of justice, alongside a sense of physical urgency, were all in place. Thank God, I used to say to myself, I’m not withstanding the invasion with a tiny book of poetry in my hands. What a miserable picture that would have been.

And it was only in certain breaches of my newly militarized routine that such things as literature, or the passion attached to it, started creeping in. It could be a briefly noticed pleasant landscape on a battered city hoarding that I would stumble upon, dawn or dusk in my dreary neighbourhood, a phrase escaping my bookshelf that had never previously been so gripping. It was even more intense after we survived the series of March attacks while watching Wong Kar Wai’s Chungking Express. As desperate as it seemed at the time and remains mind-blowing, dreaming about meandering through lemon rooms, late-night stops and cheap, gaudy hotels provided a remote heaven.

After all, why underestimate the importance of a dirty wall spot that suddenly resembles a beautiful cloud when you listen to far-flung blasts. So, while fervently advocating against any form of artistic detachment, it was in those scarred days that I surreptitiously fell in love with dreaming and writing for the first time since childhood. I was captured by the idea of being helpful, useful, enjoying the irrefutable justification for my own existence; I saw no sense in contriving words or, what’s more, in pretending that they mattered, since they couldn’t heal wounded flesh nor restore light. But, at the same time, I was desperately lured by the idea of taking a step into any sort of dimension that wasn’t mundane nor real. I dreamt about standing in the middle of streets in distant places such as Seoul and Tampa, city lights in 1990s South Korea, the national park in Singapore. Strikingly, what I recall most about those very first weeks is film stills of Korean cyclists, some of my vivid mid-morning dreams, things I haven’t actually seen, cities I haven’t visited. Somehow, despite all the contempt I felt for musings, they became the only thing I deeply enjoyed, the only thing that helped me be in my own body.

‘Who has the privilege not to know?’, spins round in my head as I write this essay. And, who has the privilege to stick to another, less traumatic and more enticing topic? Who has the right to brush off the latest breaking news and dwell on Gilles Deleuze, Renaissance Art, street vendors of the past, the soaring prices of Manhattan cocktails, issues of semiotics, the safe setting of a panel talk lying between you and the ‘controversial subject’? Do I envy them enough to loathe them?

Even though the gap between real and futile may be fictitious (albeit never strictly one nor the other), the idea of writing as a life-shaping pursuit is no longer on my mind. I guess, you can candidly call words ‘a significant contribution’ until air missiles, pharmacy receipts, jarring insects or anything else start to shape your future way more than all the books you’ve ever read. And still, dreams, as useless as they may seem, will always find their way to persist.

This article first appeared in Eurozine partner journal Glänta in Swedish. The above is an edited version of the original English text.