Belarus and the ghosts of the wild hunt

The ongoing repression of Belarusian society now extends to the banning of literary works by Belarusian writers seen as seditious. The reason can only be that they offer the regime its true reflection, writes one of the country's leading poets.

Why are books being banned and their authors not permitted to meet with readers in today’s Belarus? Why are there artists who cannot exhibit their works, and whose concerts are banned? Why do writers in increasing numbers find themselves behind bars, with the result that a significant part of our contemporary literary scene – as well as our classical writers of a century and more ago – now consists of prison literature? Why does the Belarusian language suffer discrimination, marginalisation and, ultimately, destruction even more severely than in Soviet times? And this in a country that is still called Belarus!

Some will say that this is because we have in our country an age-old, merciless war of cultures, in which one of them, believing itself to be better and superior, tries to dominate the other and destroy it. Others will maintain that we are dealing with a war against culture generally, waged by something totally bereft of any culture. I am not going to draw any final conclusions. Instead, I will restrict myself to touching upon two issues. The first is to ask how far fear of culture and hatred of books can go. The second is to ask what this culture and the books it produces are at times capable of achieving.

Calibanism

No, that is not a typo.

Oscar Wilde once wrote ‘It’s the spectator, and not life, that art really mirrors’. I’ve always thought this to be a fine turn of phrase, even if too paradoxically exaggerated. Wilde goes on to name this particular spectator, when he writes of the rage of Shakespeare’s Caliban at seeing (or not seeing) his own face in a mirror.

‘The Enchanted Island Before the Cell of Prospero – Prospero, Miranda, Caliban and Ariel (Shakespeare, The Tempest, Act 1, Scene 2)’. Source: Wikimedia Commons

I now realise that the master of paradox was not exaggerating. This year Belarusians have been able to see a Caliban with their own eyes. And not just one: they have witnessed the whole concept of state calibanism. The Miensk City Prosecutor’s office is packed to the rafters with Calibans, who in August 2023 delivered a verdict on several works of literature by naming them ‘extremist’.

It’s not only contemporary authors who found themselves on the list; so did classics of the twentieth and even nineteenth centuries. It is rare indeed for authors who died long ago to fall foul of the law today. There is, for instance, the well-known playwright Vincent Dunin-Marcinkievič (1808–1884); streets are named after him and statues erected in his honour in our towns and cities. The question of demolition of statues and renaming of streets has not yet arisen; a more ‘elegant’ solution has been found. It is perfectly possible for only one part of a book to be seen as criminal. Two verses from a little volume of our playwright’s works, and the introduction to the book written by a contemporary literary scholar. Without trying to imitate what happens in the film Dead Poets’ Society, let us now, my dear students, all tear out of our copies those pages of the introduction. Come on, don’t be shy, and don’t forget those two verses, tear them out too!

There are times when the regime’s hatred of certain authors is obvious. Take, for example, our contemporary Uladzimir Niakliajeū, who is not only a widely-known poet, but who also entered politics and participated in the 2010 presidential race. On election day he was attacked by members of the security services dressed in plain clothes and taken to the emergency department of a hospital. He was kidnapped from there, and for several days his family had no idea whether he was still alive. Eventually he was found in the KGB prison. He spent forty days there and was then kept under house arrest for several months. He took no direct part in the 2020 presidential campaign, but even so was repeatedly hauled in for questioning and ultimately forced to leave Belarus. Not for the first time in his life, he now lives abroad. An obvious extremist!

Another book viewed as extremist is the one by Łarysa Hieniuš (1910–1983), a poet who lived in emigration. After the end of the Second World War she was forcibly removed from Czechoslovakia to the USSR and sentenced to 25 years in a labour camp. She spent eight years there. But her spirit was never broken. She continued to support other prisoners with her poetry. They came to regard it as ‘glucose’, so great was the strength they derived from what she wrote. After being freed, she refused to take Soviet citizenship, and lived out the rest of her life under surveillance by the security services. She has never been rehabilitated. All that has been done is to officially reduce her sentence to the period she actually spent in the camp. Without doubt an extremist!

Then there is the book by another poet in the diaspora, Natallia Arsieńnieva (1903–1997). Her patriotic prayer-like poem ‘Almighty God’ has been the unofficial anthem of several generations of the Belarusian opposition, but it reached the height of its fame during the Belarusian street protests of 2020. This was the hymn performed by masked musicians and singers wherever people gathered; it was from these protest performances that the famous ‘Free Choir’ eventually grew. Of course, the author of a work that is extremist in every single note could not be anything but an extremist herself.

The Calibans from the Prosecutor’s Office could deal with all these. But now begins the most interesting part, the point at which they have to face a mirror. The fifth item on the list of extremist literature is the collected works of Lidzija Arabiej (1925–2015), a writer that one would have thought absolutely harmless for the regime. I was amazed when I read about this because I had grown up on her children’s writings and saw nothing seditious in them. A few days later I located a copy of the ‘condemned’ book in question and began to leaf through it carefully – and I was dumbstruck again when I came across her story ‘The white Pomeranian’.

It is necessary at this point to make a brief digression into the study of Man’s Best Friend. The nub of the issue is that the third place on the list of the best-known sources of jokes and memes in Belarus, after the illegitimate president and his equally illegitimate son Kolia, is occupied by a little white Pomeranian. His name is Umka and he is a house pet. Apparently Łukašenka’s most reliable friend, Umka first started appearing on Belarusian news broadcasts in the spring of 2020. That is to say, a few months before the routine falsification of elections and the explosion of protests and repression. At the height of the pandemic.

In April 2020 the dictator – one of the few leaders in the world to openly deny the existence of the coronavirus – was peacefully planting pine trees for the benefit of television cameras; and in a basket there was a little white dog. It wasn’t long before conspiracy theorists maintained that the pair of them – the little dog and his master – were intended to draw Belarusians’ attention away from the problems of the pandemic.

In another TV programme Łukašenka was seen chopping wood while the white Pomeranian ran around barking. He (the Pomeranian, not Łukašenka) could later be observed sitting on the table like the lord of the manor, taking tid-bits from plates while his mate was giving an interview to a foreign journalist. On the feast of the Baptism of Jesus, Łukašenka even offered him some holy water to drink; regrettably, the white Pomeranian refused to partake. And so it was that a third camera-ready newsmaker emerged in Belarus, after ‘Kolia’s daddy’ and Kolia himself.

This is where Lidzija Arabiej’s story comes in. Let us try to picture the reaction of the Calibans of the Prosecutor’s Office. They see that terrible title in the book’s list of contents, they open the book on the right page and find that they are not hallucinating, but that there really is a story called ‘The White Pomeranian’. To make matters worse, it ends with the even more frightening words, ‘Drop dead, you bastard’. It’s no longer of any interest to anyone that the remark was directed at neither the Pomeranian nor his master.

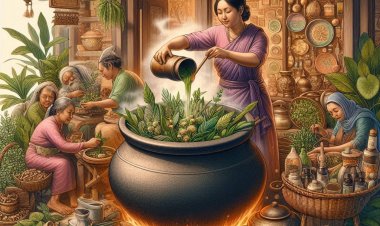

The 1975 takes readers back to the Miensk winter of 1943 under Nazi occupation, to the hunger of the time, and to the black market as the only means of not dying of it. A woman brings to market a pot full of mouth-watering hot potato pancakes… At this point the Belarusian heart of the censors starts to beat joyfully, they almost manage to calm down, but unfortunately that wretched white Pomeranian makes an appearance. And not only that, he’s lost his master.

What’s this, then? ‘It has lost its master.’ Does it mean that they, officials of state who know only how to seek whatever is not permitted and then forbid it, have lost their employer? What are they to do? Their empathy for the hero of the story grows hugely, while at this very moment the Pomeranian himself … Let me quote the ‘extremist’ Lidzija Arabiej:

Then the dog turned to the woman, the dispenser of the potato pancakes, and, as if he had suddenly remembered something, sat up on his hind paws and began ‘sitting pretty’. He tried hard to beg in this way for some time, he seemed pleased to be able to remain so long in what was for him an uncomfortable pose, his eyes gazed at her with devotion and sincerity, joy and hope…

His front paws hung trembling like rags, his pink tongue trembled – there was drool dripping from it, the dog was making a huge effort to maintain his position, it was as if his whole body was saying: look at how hard I am trying for you, how hard I want to please you, I surely deserve a reward, don’t I?

‘Clear off.’ At last the woman had had enough and brandished a fork at him.

No two ways about it, that’s a frightening prospect. Ban the book at once! But then the state-appointed readers see how the story ends. The little dog has another feeling, one that is stronger than hunger. Suddenly he sees a member of the occupying forces walking by and begins to bark at him with all his might. The man in a foreign military uniform takes fright and retreats. This delights the Belarusians at the market so much that the little dog receives an unexpected (and long-awaited) reward:

The dog continued to stand and bark at him as he retreated from the scene; he barked with all his doggy might, he barked until he was hoarse, until he despaired of ever barking again. When he had quietened down a little he heard an unknown voice behind him:

‘Who’s a good doggie, then?’

And a piece of warm, fragrant pancake plopped down on the snow in front of him.

And that same voice went on:

‘What a clever little pooch. Drop dead, you bastard.’

Serious researchers of Lidzija Arabiej’s work may quite possibly object to what I say and offer a different explanation for her ‘extremism’. They will mention stories in the book that deal with the epoch of Stalinism and repressions, with the sentences handed down to ‘enemies of the people’ and the families that were separated when the children were ordered to renounce their ‘criminal’ parents or given new names and life stories, so that it became impossible for the parents to find them even after rehabilitation. They will mention the story One Cold May which portrays the work of the secret services, who force people to spy on their nearest and dearest and denounce them. I will agree with them and add that the present-day servants of the dictatorial regime feel themselves to be the heirs and successors of Stalin’s thugs; that explains why repressions have once again become a taboo topic.

Nevertheless, I enjoy imagining how this particular story about the white Pomeranian was the one that our Calibans’ eyes stumbled across, and how they realised that masters unavoidably die and that their lackeys are left with nothing after years of service on their hind paws except being told to ‘clear off’. They’ve long had a choice in front of them; either go on serving or start barking. I think they must have experienced a surge of rage at the author when this thought occurred to them. However, the thought is now stuck in their heads and isn’t going to go away.

Letters of Hope

Uladzimir Karatkievič (1930–1984) is the writer of whom Belarusians are most fond; his works are not yet burning on bonfires or hidden away in special classified, closed library collections, and have not even yet been deemed extremist. However, his most famous novel, Ears Of Corn Beneath Your Sickle was this year suddenly withdrawn from the school syllabus. Perhaps this was because the Calibans could see themselves unmistakably reflected in the author’s mirror and realised the threat.

The novel is devoted to the spiritual and intellectual maturation of the Belarusian elite, to the younger generation who took part in the anti-Russian uprising of 1863. The uprising was savagely suppressed by imperial troops, and its leaders annihilated. One of them was Kastuś Kalinoŭski, included by Karatkievič as a character in the novel. This may explain why the author completed the first two volumes of the book but did not finish it; he was unable to take events up to the murder of his beloved heroes.

This novel, along with other works by Karatkievič, acquired cult status. In the Soviet times people would queue outside bookshops whenever a new book of his appeared. (The writer himself said, ‘You need to write in such a way as to make people steal your books from libraries. They steal mine.’) His books made such a powerful impression on readers, especially young people, that they began to take an interest in Belarusian history and culture. Even if they had been raised in Russian-speaking families, they often switched to using Belarusian.

In 2020 – on the eve of the falsification of the presidential elections and the ensuing mass protests and brutal repressions – Belarusian internet users frequently quoted one particular extract from the novel. It sets out the true nature of Russian imperial reactionary policy in the middle of the nineteenth century:

It was a terrible, hard time.

The entire immense empire had already been lying moribund for twenty-six years, ice-bound beneath a horrifying political frost that heaved like a great shaggy beast over its vast expanses. Those who tried to take deep breaths would freeze their lungs…

…There was no happiness anywhere.

Everything was sacrificed to the idol of state power.

The keywords here are ‘twenty-six years’; in 2020 this was exactly the length of time that Belarus had been ruled by an illegitimate president. After the routine falsification of the election and the regime’s suffocation of our attempt at an uprising, repressions were intensified to an unprecedented level of savagery, the remaining vestiges of legality finally ceased to operate, and the Russian imperial presence in Belarus became much more visible. The start of Putin’s war against Ukraine demonstrated that a politically independent Belarus no longer exists; the puppet dictator, now almost completely under the control of the Russian aggressor, is free to act in one area alone – administering unrestricted terror to his own people. There are thousands of prisoners of conscience, some of whom die in prison in mysterious circumstances. Hundreds of thousands of Belarusians have been forced to leave their country, those who stay behind live in inward emigration. None of them can stop rockets flying towards Ukraine. There is a metaphor that can be heard more and more often: Belarus is in the grip of a ‘wild hunt’.

The metaphor sends us yet again to Karatkievič, this time to his ‘gothic noir’ novel King Stakh’s Wild Hunt. You can argue to your heart’s content about how exactly to explain attempts to bring literature and reality closer together. How much do they depend on writers’ perspicacity or ability to formulate things that are universal and therefore always vital? Or how much depends on the story itself, one that goes round and round in a circle and gives us no chance ever to break out of an eternal nightmare. Either way, every conscious Belarusian is aware of just how much more relevant the Karatkievič story has once again become. It is a story of colonial pressure. Of the degradation of an ‘elite’ that suppresses its own people while abjectly serving the foreign masters. Of how a fear is engendered that paralyses and enslaves.

Johann Wilhelm Cordes , ‘Die Wilde Jagd’ (The Wild Hunt), 1856/57. Source: Wikimedia Commons

However, it is also a story of the cultural role of intellectuals in returning to us memories that had been almost totally erased by the occupying aggressors. A story of the strength of the powerless. Of non-violent resistance which may one day no longer be enough, and then there will be no option but to respond to violence with violence. Of the ‘soft power’ of love that prevents us from going mad when the darkness is at its most oppressive. Of solidarity and mutual support among those who are threatened by a common enemy. Both Belarusians and Ukrainians are involved in the Karatkievič story, just as they are in real life today.

The Belarusian Karatkievič entered the Taras Shevchenko University in Kyiv as a young man. Here he came under the influence of intellectual friends who were deeply involved in the study of Ukrainian culture; they inspired him to take a stronger interest in the culture of Belarus. He at last conceived the idea for his novel and began to write it. The theme of Belarusian-Ukrainian unity runs right through it, and there are certain autobiographical elements in the figure of the young intellectual Andrej Śviecilovič, a former student of Kyiv University. Here is his dialogue with the novel’s protagonist Andrej Biełarecki:

‘Why did they exclude you from the university, Mr Śviecilovič?’

‘It all began with an event in memory of Shevchenko. Students of course were among the first. The authorities threatened to bring in the police,’ he even blushed. ‘So, we started shouting. And I yelled that if they so much as dared do such a thing within our sacred walls we would wash the shame from them with our blood. And the first bullet would be fired at the man who would give such an order. Then we poured out of the building, there was a tremendous hubbub, and I was grabbed. When they questioned me at the police station about my nationality, I answered, ‘You can write that I am a Ukrainian.’

‘Well said.’

‘I know that it was very risky for those who had joined the struggle.’

‘No, it was good for them too. A single answer like that is worth ten bullets. And that means that everyone is against the common enemy.’

The young Belarusians who after the presidential election in 2006 – inspired by the Orange Revolution – put up tents on October Square (that they renamed Kalinoŭski Square) had undoubtedly read Karatkievič. As indeed have those who are now fighting for Ukraine in the Kalinoŭski Regiment.

Against the background of war, a perfectly understandable process of renaming Ukrainian streets got under way. The Ukrainian literary scholar and translator of Karatkievič, the poet Vyacheslav Levytsky, put forward a proposal to change the name of Dobrolyubov Street in Kyiv to Karatkievič Street. His proposal was eventually adopted.

This is what Levytsky wrote:

I hope that a street bearing this name will help to smooth over at least some of the misunderstandings between Ukrainians and Belarusians who oppose dictatorship. I would like this renaming to be evidence of our respect for and gratitude to the Kastuś Kalinoŭski Regiment, Belarusian partisans and all those free-spirited Belarusians who find opportunities to aid Ukrainians.

Many thanks to Vyacheslav and to everyone in Ukraine who voted in support of his proposal! By the way, there isn’t a street in Miensk named after Uladzimir Karatkievič. I don’t need to explain why not, do I?

On the other hand, two whole operas have been based on the Karatkievič novel King Stakh’s Wild Hunt. The first was written by the composer Uładzimir Sołtan. The premiere took place in the Miensk Opera back in 1989. It was revived in 2021, expanded with material from the composer’s archive and with new sets and special effects in the Gothic style. However, life itself proved to be the main Gothic special effect: the staging of the opera collided with the Calibanist censors.

The issue here was a crucial phrase cut out of the libretto when the riders on the wild hunt frighten the mistress of the palace with the call ‘Raman in the twentieth generation, come on out!’ This may conceivably be because, on 12 November 2020 at the height of the protests within the courtyards of apartment blocks, Raman Bandarenka was beaten to death by ‘persons unknown’. He had gone down to the yard in front of the block where he lived, leaving a note on his Telegram chat ‘I’m going out!’ His murderers in masks were suspiciously reminiscent of the antiheroes from Karatkievič’s book.

The second version of the opera appeared this year, and I was fortunate enough to work on the libretto. The music was written by Volha Padhajskaja, the directors were Mikałaj Chalezin and Natalla Kalada, and the conductor was Vital Aleksiajonak. The premiere was held on the stage of London’s Barbican Arts Centre. It is difficult to imagine a more fitting ensemble for today: actors from the Belarus Free Theatre that continues to exist in forced emigration and Ukrainian opera singers.

The Belarusian actors spoke their parts, and the Ukrainian participants sang – in Belarusian. It was essential for Belarusians to hear this now, at a time of trials, traumas, wrongs and artificial divisions. I think that it was important for the Ukrainians too to hear about how much Ukraine meant to the beloved Belarusian writer.

I had the privilege and pleasure of working with the Ukrainians on their Belarusian pronunciation. Our languages are very close lexically, but completely different phonetically; it is very easy to tell when a foreigner is speaking. The musical ear of the Ukrainian singers had a role to play here: their pronunciation on stage would be the envy of many citizens of Belarus.

I cannot say whether it was the magnificent composer or the outstanding singers Tamara Kalinkina and Olena Arbuzova who played a greater part in making the character of Nadzieja Janoŭskaja in the opera more powerful, emancipated and vivid than the rather passive image of the heroine in the original book. In my humble opinion Nadzeja’s parts were the most powerful and unforgettable. Quite possibly, anything else would have been unthinkable after the protests of 2020 and the role women played in them.

The premiere was attended by Belarusians from various cities, countries and even continents, the Belarusians and Ukrainians of London came, but most of the audience was British. There were four performances, each one played to a full house. After each performance there were shouts of ‘Slava Ukraini’ (Glory to Ukraine) and ‘Žyvie Biełarus’ (Long live Belarus), and of course back came the replies ‘Heroyam slava’ (Glory to the Heroes) and ‘Žyvie viečna’ (May it live forever).

Awaiting the audience, there was on each seat a ‘Letter of Hope’, a postcard in an envelope prepared by the organisers, designed and signed by Ukrainian children who had suffered from the war. Some had lost their home, some of them had lost their father at the front, some had lost both parents in a bombardment. However, in the letters there are no complaints of pain – quite the opposite, they show a desire to support those who read them; perhaps the readers are also going through a difficult time. There are expressions of love in them, even an urge to joke.

‘There are times when you have to lose something in order to find something new,’ writes Lev, fourteen years old.

‘Don’t worry, I’ll always be with you,’ writes Sasha.

‘Be kind and kindness will come back to you,’ writes Valik, nine years of age.

On his postcard Artyom from the Kherson region has this to say: ‘Never give up. Respect your parents. If you don’t respect them, I’ll come and bite your ear off.’

The Barbican theatre seats 1,500 people; four performances mean 6,000 letters. I collected four of them and keep them safe.

This translation was supported by the S. Fischer Foundation. The article was first published in Dekoder in German as part of the series ‘Belarus – glimpsing the future’.