A recipe for survival

Veganism, the ethical choice, was once born of necessity. Today’s regular omnivore diet was previously a luxury for the wealthy, ill afforded by peasants. Preserving food was a means of subsistence. Can pickling and jamming traditions, now making a comeback, be recognized for their cultural heritage in addition to gentrified sauerkraut and cherry compote recipes?

September. People, flies and wasps cling to the last of the blackberries and the first soft pears of autumn, while cherry plums and mirabelles lie putrefying on concrete pavements. Their sharp vinegary smell reminds us that it is time to say goodbye to summer and prepare for the coming of winter. So, go on! Order a few kilos of purple plums from the greengrocer’s or bring them over in crates from the family orchard. Or else you can lug them over from the neighbour’s allotment in reusable supermarket bags. Their skin must feel firm under your fingers and the juicy, honey-coloured flesh should coat the tongue with its stubborn, acidic sweetness. This is crucial.

Then it will be time to call your friends to boast about your takings and invite them to share in your labours, assuring them that the plums are locally sourced and (almost) certainly haven’t been sprayed. Just make sure they bring their own knives. The fruit is best cleaned in a single batch, under the shower or in the bath. Jars should be steamed in a dishwasher along with knives.

Once last year’s jar lids have been found, they are best boiled in a saucepan. The rusty ones must be discarded.

Now cut the clean plums, remove stones and place in large, wide saucepans or in a heavy frying pan. Do not peel or sweeten. Lower the heat, have a chat about inflation and, even though you may be losing some of your initial enthusiasm, stir the fruit with a wooden spatula until the juices run.

Continue until the mixture boils, disintegrates and is transformed into a luscious purple paste, which should stick to your spoon but come away easily from the base of the saucepan. A kilogram of purple plums will produce one jar of powidl spread, possibly two. It is therefore advisable to pre-set some rules and divide the spoils equally among the workers, so no one goes away empty-handed. Fair distribution is the very foundation of this kind of enterprise. Some labourers do the cutting, others stir, others still gossip. Somebody will doubtless let out the dogs and the children because they’re so bored, or go to fetch a friend who’s running late because she overslept and then got lost in a maze of roadworks. The best, most adroit workers should be despatched to fill jars with boiling plum powidl – preferably armed with a spoon, a wide funnel and nerves of steel.

Powidl: thick, unsweetened plum marmalade. You stick a spoon into it and you’ve got a popsicle. It can keep for years and is essential for many festive bakes across eastern Europe.

Do not overfill because, when the mixture is pasteurized, the jars may explode. Pasteurize the entire batch in a cold oven, heated gradually – with jars tightly closed – to a temperature of 130 degrees centigrade. Once the required temperature is reached, cook for half an hour, then cool in the oven until room temperature is restored. For your own peace of mind, finish by placing the jars upside down, on their lids, so they are nicely drawn in.

After that, there’s the clearing up to do, but the sight of a work surface covered with jars of powidl may offer some sort of compensation. Rather like the thought that one day we will all be grateful to one another for having made the effort. Because preserves, time-honoured as they are, represent the food of the future. They are a simple booster in times of trouble, uncertainty, instability, scarcity, hunger, fear and poverty. They preserve life.

Veganism, necessity and want

The connection between veganism and basic human need is powerfully highlighted in Joanna Kuciel-Frydryszak’s book Peasant Women (Chłopki). It makes me flush as I read it because, essentially, this is a book about my own family. It offers a window into the lives of the aunts and grandmothers of so many of us in Poland: ‘strong hard-wearing women’ with ‘legendary foresight and an extraordinary capacity for sheer slog’ to whom we owe the fact that we are still here.

They worked a full eighteen hours a day, ‘which is to say over 15% longer than men’, no matter how hungry they were or how cold the conditions. They laboured in the fields, looked after animals, cared for children, cooked for the family, cleaned, mended, span, milked, and embroidered. There was no respite and this went on throughout their lives.

Our best-loved preserves have an unhappy history, as Kuciel-Frydyszak shows:

The countryside fed the cities, but failed to feed itself… you had to know how to make use of anything edible, no matter how hard and stringy it was. The prices of country produce were constantly falling dramatically, and everything else was increasingly expensive. As food producers, country women did not eat the animals they bred, unless they were comparatively rich… Daily fare consisted of potatoes with cornmeal or pulses.

This version of veganism was inspired by necessity, not choice. It was badly balanced – with ‘soups’ made solely of water and sorrel, for example – and often based on products that had gone off, such as overboiled noodles or pancakes made from rotten potatoes. Stuff like this could be used up at home because no one would buy it anyway.

Between 1918 and 1939, in the Second Polish Republic, many women had little idea about how to make preserves, but almost all families prepared for winter by making sauerkraut … Neighbours would come over with their well-used barrels which sometimes leaked or had missing staves … A damaged barrel would have to be mended and then the women set to work. After the cabbage has been well salted, they’d look around for a child with clean feet which would fit into the barrel and do a good job beating down the contents.

A century on, Marta Dymek published her book Food the Polish way [Jadłonomia po polsku] which has come to be regarded as a plant-based cookery bible in Poland. When presenting her sauerkraut recipe ‘for contemporary cooks’, Dymek wrote:

A few years ago, if anyone had told me I should be making my own sauerkraut, I’d have dismissed it as absurd. How much can you do, after all?.. But the result proved delicious. It can be served on sandwiches with hummus, in a bagel with pâté, or straight out of the jar. Home-made is completely different from the variety sold in shops, or even at the highest quality greengrocer’s. It is firm, fragrant and crunchy, like treading on freshly fallen snow. Pickling cabbage is simple and requires no special equipment or conditions at home. You can pickle in a studio flat or an IKEA kitchen, and you can certainly do it for one.

Dymek’s recipes blend cabbage with turmeric, cinnamon or fresh cranberry – but not for the purposes of culinary gentrification. Her intention is rather to restore dignity to dishes and culinary practices which have come to be associated with poverty, since the time communism fell and ‘world food’ sections appeared in urban grocery shops. In dreaming up cabbage recipes ‘for contemporary cooks’, Dymek seeks to prove that pickling is more than just a dull, and gruellingly work-intensive, relic from a past marked by relentless food shortages. It is a precious cultural legacy. It would be a pity if the sauerkraut tradition vanished only to be replaced by kimchi.

Culture wars: sauerkraut versus kimchi in the intercontinental contest of cabbages.

The deficiencies of country life

How is it that the labour-intensive, lacklustre dishes which once served as staple foods for the poorest in Polish society, have moved into the repertoire of urban cooks to be served up at dinner parties given by middle- and upper-class literati? It seems to me that Kuciel-Frydyszak could be on to something when she points out that, as the granddaughters and great-granddaughters of peasant farmers’ wives, we associate the taste of pickles less with hunger and poverty, than with a nostalgia for childhood.

We remember summer expeditions to the allotment and winter descents deep into the cool, clammy darkness of the cellar. We recall the warmth and security of a grandmother’s cooking, that feeling of fullness and satisfaction.Consider Maciej Jakubowiak’s account of his grandmother’s life in Dwutygodnik (coming soon in English in Eurozine!), written as he was trying to unravel the cultural and national story behind his family’s susceptibility to obesity:

Albina knew about want. And so, when she became a mother, she promised herself that her child would never go hungry. She fed it (that is to say Hanka) with cartloads of food, so no one would ever see the child’s ribs, so the child would grow, so it would have energy and fat to spare. And, sure enough, it did.

No surprise then that Jakubowiak’s childhood, like that of so many of us, was defined by gathering and preserving food products:

There would be kilo after kilo of green beans, new potatoes, peas, cabbages, field cucumbers, raspberries, strawberries. Everything was brought down from the allotment starting late spring and throughout the summer months. As the end of the holidays approached, there would be a surge of activity. The produce had to be preserved and bottled, the cucumbers pickled, and sweet syrup poured over the strawberries and raspberries.

Production on this scale would have been impossible for a homemaker working on her own, no matter how determined or skilled she was. The more so as she would have been living in a country only that was only partially electrified and, in many places, without sewers. Under these conditions, as Małgorzata Szpakowska explains in To want and to have (Chcieć i mieć), all work related to managing a household expanded ‘to epic proportions’.

The lack of basic infrastructure in villages and small towns meant that entire communities had to be involved in managing and preserving locally sourced produce. Every generation was called to contribute: women, men, grandparents and grandchildren, not to mention the neighbours and work colleagues.

Szpakowska emphasizes the integrative effect of this kind of grassroots teamwork in a country decimated by the Second World War and scarred by forced migration. The production and exchange of homemade and ‘homegrown’ preserves, certainly helped feed the family in times when rampant inflation and shortages were rife. But it also tamed post-war urban reality, created new social links, and helped replace a lost past. It offered people a sense of home in an alien world.

As the Polish People’s Republic established itself, after 1947, our grandmothers and great-grandmothers acquired allotments and moved, or were forcibly transferred, from rural areas to cities. In an unfamiliar urban environment, they were expected to cook differently, in ways that were healthier, more varied, yet still ‘traditional’. That is to say, in the way servants armed with juicers, meat grinders and food mincers once cooked for the richest sector of pre-war Polish society. Kuciel-Frydryszak leaves us no illusions:

Taking pleasure in food was traditionally a privilege of the nobility.

Peasant women ate not to enjoy the experience, but to have the strength to go on working. Insofar as they ate at all, that is, because men, children and animals always had priority.

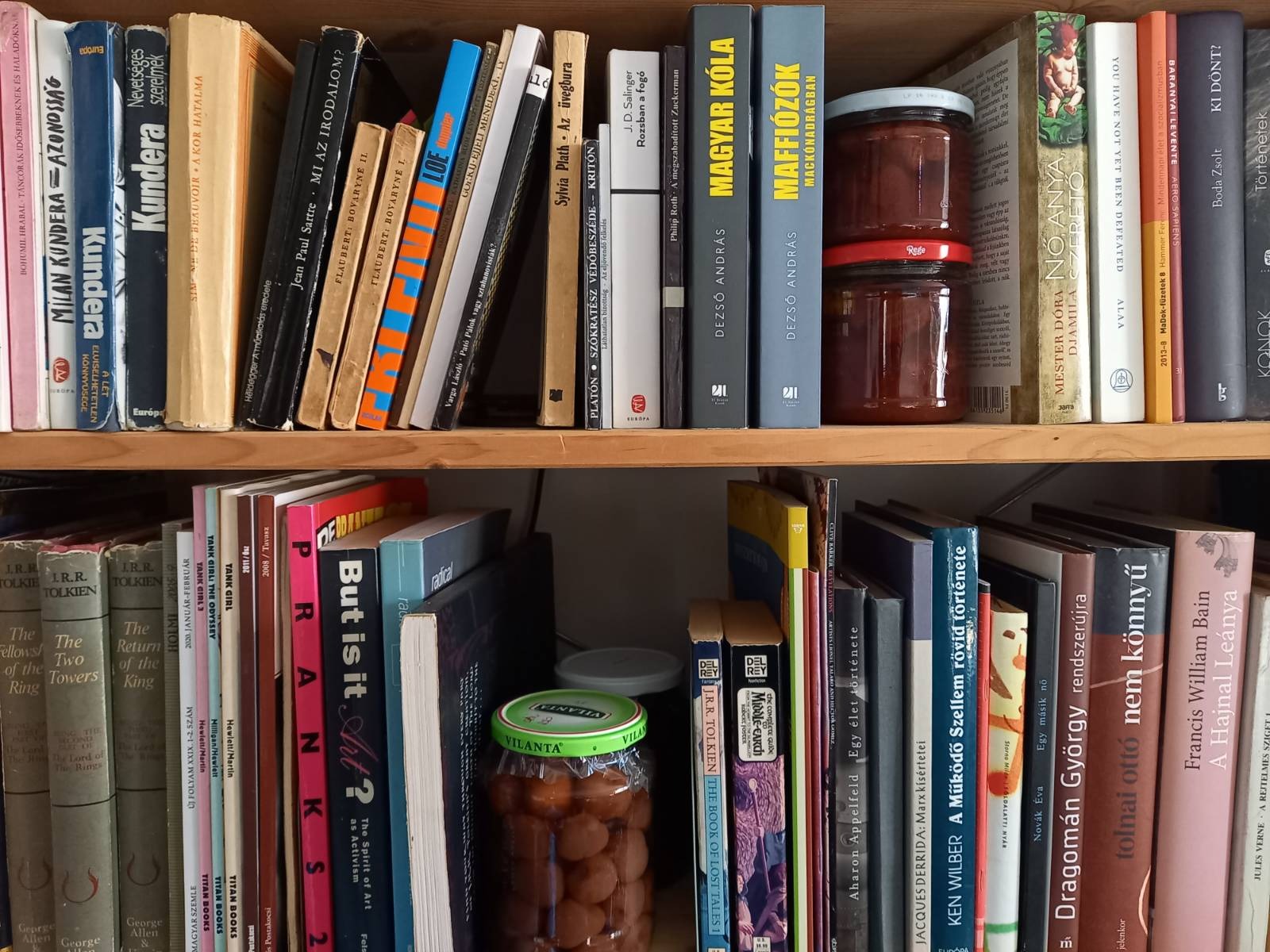

Cultural heritage in mixed media: sour cherries, strawberries and paperback. Preserves on a Hungarian household’s bookshelf.

Methods for preserving food, which we associate with country living and think of as ‘traditional’, were in fact learnt from educated urban women: landed gentry, regional campaigners, former house servants and mentors of country wives’ groups, who went into the countryside in the 1930s with a mission to ‘civilize’ rural communities. More recently, the cookery author Marta Dymek visited similar country wives’ groups while working on her book Food the Polish way – a handbook of recipes for traditionally seasonal, plant-based dishes which many of us will remember our grandmothers cooking, although the reassuring comfort they offer is illusory because they were invented in response to poverty and widespread shortages. Marta Sapała writes about these unacknowledged skills in another book entitled Wasted (Na marne), which examines the astonishing scale of modern food wastage. The words she uses to address one of her forebears are profoundly moving:

You could, if you wanted, run workshops on “cooking for survival” – the kind that cost at least 100 zloty to attend, and get publicized in social media or magazines about the good life, full of sophisticated graphics… Even now, as you walk home through the beech forest where pigweed grows by the lake… you are tempted to pick some. How do you cook it, people would ask? Oh, just fry it up in oil! It’ll be really tasty, with a nutty sort of flavour. Or you can have it with eggs, in an omelette if you want. After all, eggs are easily available now. They were rare once, a delicacy.

You can read Marta Sapała’s article on refrigeration and food preservation in Polish original in Dwutygodnik or in English in Eurozine.

Poisons that won’t be rinsed away

Pasteurization was a channel for social mobility. It encouraged emancipation: it fermented hunger and shame, it bottled feelings of pride and personal resourcefulness, it colonized the gut of an entire social environment with bacterial flora and life-giving yeast. This was ecological solidarity of the purest kind – washed, peeled, chopped, blanched, and locked in a glass jar rather than a plastic tablet.

Preserve display in a private home. Jams, marmelades, compotes, pickles and syrups.

Am I exaggerating? Am I projecting my personal, modern sensibilities onto past practices when the two share nothing in common? Am I rewriting history through my analysis of Polish food culture, or looking for enlightenment in the shadow of ignorance? After all, our grandmothers couldn’t possibly have been aware of how pickles affect the microbiome, or understood their environmental significance, right? Right?

Not entirely. When I look through cookery books about preserving food, published between the 1960s and the 1990s, I am struck by how much space is given to the popularization of scientific know-how, not just about fermentation but about the ecological environment. Take Irena Gumowska’s The sun in jars (Słonce w słoikach) which accompanied my grandmother, year by year, in her unceasing crusade to preserve food:

As everyone now knows, preserves should not be made out of fruit grown in a toxic environment. Poisonous substances cannot be rinsed away or removed, and their toxicity may increase as the product becomes increasingly dense. It has been shown that wild berries are non-toxic only if they grow more than 30 metres away from the road. In many cases the safe distance can be as much as 500 metres… Fruit and vegetables from allotments situated in Kraków have been found to contain 2 to 10 times more heavy metals than crops grown in gardens or fields 30 kilometres from the city… Vegetables grown in Silesia have 2 to 9 times more cadmium, and 2.5 to 4.5 more lead, than vegetables from allotments in Kraków. That’s the way it is.

Everyone now knows. That’s the way it is. It’s obvious. Ecological consciousness, and the nous it takes to survive in times of climate change, are scarcely novelties in the Polish context. These skills did not come to us from the West, irrespective of how often we talk about a ‘fashion’ for the slow life, zero waste, DIY or degrowth. It’s not in France or the United Kingdom, but in our grandmothers’ flats, in the huts where our great-grandmothers lived, and in the market halls of Ukraine, Georgia and Kazakhstan today, that tables are precariously weighed down by containers brimming with pickled vegetables, sugary fruit conserves, or traditional Jewish marinades. Preserves are the expression of fermenting regional cultures.

A rural aftertaste of war

Olia Hercules writes about this regional ferment beautifully in Flavours of the countryside (Sielskie smakiv) a cook book rooted in the riches of Ukrainian country summers:

In Ukraine today you can find Transcarpathian villages in which Hungarian, Slovak and Polish dishes appear on the table beside Ukrainian national dishes such as borscht and stuffed dumplings (varenyky)… Landscapes change along with the people… The northern marshes are full of blueberries, cranberries, sea buckthorn and wild rose… Herbs growing in the Lviv region are different from those in southern areas of the country. You can’t often get fresh coriander, but thyme and marjoram are available everywhere. In June the markets in Lviv display jars of sweet wild strawberries covered with fern leaves… Central Ukraine offers a selection of foods covering a range of regions – produce of the north such as mushrooms and parsnip, or pears, peaches and apricots, which love strong southern sunlight. The land around Poltawa is well known for traditional local ways of preserving fruit, which are probably the most interesting in the country…

The Dnieper River is crammed with lobsters, zanders, carp and catfish. The region is also known for the huge pink tomatoes it produces. Cottage gardens grow aubergines, paprika (both sweet and hot), a range of herbs, rhubarb, cucumbers and sweet potatoes that taste like confectionery and smell so good that they can be eaten without oil… The steppes of Kherson, where I come from, are famed for their watermelons… These get pickled too, as do apples which are mostly marinated in brine or pumpkin pulp.

Hercules published Flavours of the countryside in 2020. Three years later the Russians blew up a dam on the Dnieper, destroying one of the largest irrigation systems in Europe and, with it, countless kilometres of grain, vegetables and fruit. In the Kherson region, Hercules’ home, over two thousand hectares of forest burnt down.

As Olena Kryvoruchkina, head of Ukraine’s Operational Headquarters for the Removal of Ecological Crimes, has emphasized, soil samples taken from various parts of the country have revealed the presence of heavy metals in dangerous quantities. Air quality is also in freefall because of toxins emitted by rockets and drones. And if an uncontaminated garden or orchard is still to be found anywhere in Ukraine, it’s unlikely that anyone will be gathering its harvest or preserving its produce because so many salt and sugar factories have been blown up.

Consequently, the pink tomatoes, the cucumbers the size of aubergines, and the sweet potatoes that taste like confectionery will simply rot. And if, amazingly, anything gets preserved and bottled, it will end up in cellars packed with people sheltering from Russian attacks, sometimes for weeks. To help those affected by the war, Hercules now organises fund-raising and cookery workshops, sharing out the profits between medication and food supplies for civilians, and arms and equipment for the Ukrainian military (her brother is in the army).

Her fermentation classes – recorded in her ill-lit London kitchen at night, after her son has gone to bed – have generated special interest. On the screen, Hercules can be seen hugging a selection of ripe tomatoes to her breast as, with her other hand, she imitates the energetic way in which her grandmother would have chopped them, if she were standing there beside her rather than taking cover somewhere in Ukraine. For 200 zloty a month, you can get unlimited access to her archive of recordings through her Patreon page, and support the battle waged by Ukrainian women against their occupiers while learning, step-by-step, how to pickle aubergines, peppers, watermelon or sweetcorn.

It is a poignant form of resistance, especially if one remembers the worn and wrinkled hands that once sliced cabbage into fine threads, chopped squash into perfect cubes, or peeled the broken skin off pierced and blanched tomatoes. Or pitted cherries. Or slid tiny, firm currants off their thin, green stems.

Hope preserved

I can taste my grandmother’s seasoned cherries on my tongue, even today. We drank the syrup with our lunch and ate the swollen purple fruit separately. It was slippery, though the texture was uneven, and we always preferred to use our fingers and eat straight from the jar. Granddad would bring the bottled preserves up one by one, because otherwise, the contents might disappear too quickly. And, long afterward, when we had grown out of our children’s clothes and moved out of Poznań – where our grandparents stayed to the end of their lives – we would leave their house with a few, or sometimes dozens, of fizzing fermented pickles and preserves, depending on whether we had made our visit by train or car.

The last batch found its way to our home in Warsaw in 2008. It had been brought over by my grandmother’s younger sister. A few days after her arrival, I went down to the larder after yet another sleepless night, hoping to shake off my woes with some of my grandmother’s cherries. A quarter of an hour later I heard that my grandmother was no longer living. She had died as I was prying away the lid from a jar she had only recently sealed. That was when I understood that food is no cure-all. It heals neither depression nor mourning. Nor, for that matter, inflation, war, or climate change.

But preserves can see us through. They will help people survive another winter in a country overrun by enemy tanks, often with no electricity and not enough drinking water. They continue to bring relief on the Polish-Belarusian border, where volunteers work to save the lives of migrants by distributing hot preserved soup, despatched from western Poland by people who feel a closer affinity with a Kurdish woman who is expecting a child than with the inhuman migration policy of the Polish authorities.

Preserving food can also improve life in urban areas where – in line with new recommendations from the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) – we should be setting up more cooperative farms and community gardens. These will recultivate soil, improve water retention, decrease the environmental costs of food production and transport, and counteract the parallel epidemics of obesity and malnutrition.

We simply cannot afford to continue treating preserved food as a useless relic of the past. Go get those plums while you can! Call your friends, bring out the jars, hide away your favourite kitchen blades, and never fear that what may be coming will prove too hard to swallow!

I guarantee that our children will learn to love what the future brings, with its tang, the sourness that puckers the tongue. It won’t even occur to them that this is the taste of want. Because, for them, scarcity and need will represent the world in its entirety, as it once did for us.

Translated by Irena Maryniak. Read the Polish original in Dwutygodnik here, or our other articles in English from Dwutygodnik hereby.