Desperation for refrigeration

Kitchen white goods – ubiquitous modern appliances revered for lightening household chores – are seen as a necessity. The fridge, in taking on bulky proportions, has transformed from basic food storage utility to luxury item. Has what was once practical, yet conceals greenhouse gases, become a guilty environmental consumer trap?

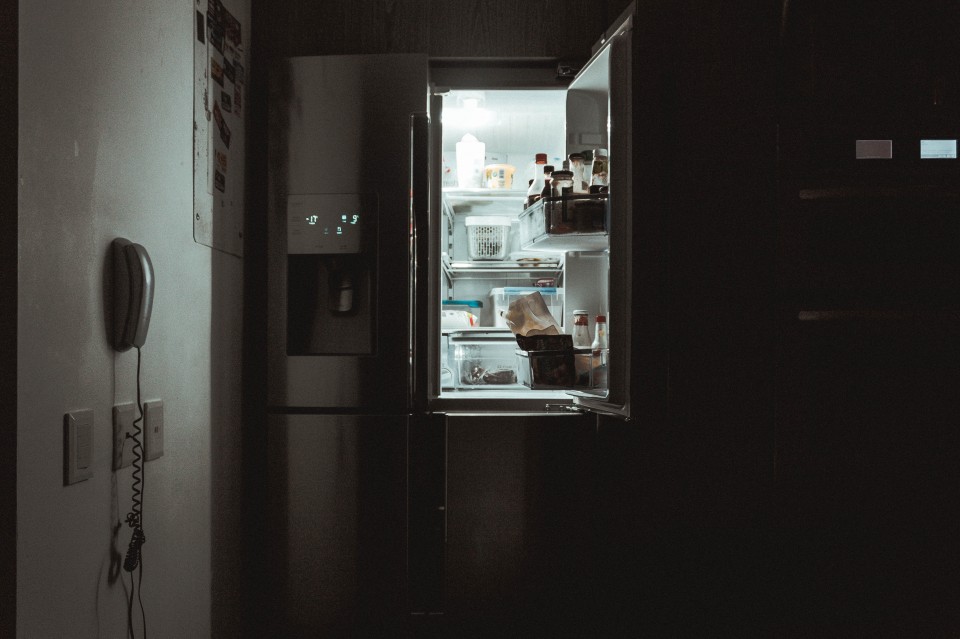

It whirred away for six years, then one day it just froze. The humming stopped and the next 24 hours saw the temperature inside slowly equal that of the kitchen. Its refrigerant had dissipated into the atmosphere. The repairman who topped it up pocketed a handsome fee, declaring: ‘I can’t provide you with a guarantee, because the gas could well leak out again by tomorrow.’ Two days later it had done just that. It was the end of August and hot, but I thought: what would it be like to live without a fridge at all?

A cool embrace

It took me a few days to adjust to this new way of living. I mercilessly threw things away; what had previously been suspended had suddenly begun to decompose. Then I started shopping carefully: microscopic quantities, with a specific day in mind. I prioritized eating whatever looked like it was losing its vitality. And after finally converting the orphaned vessel into a wardrobe, I let the world know on Facebook, using a stock photo to illustrate it: a void draped in a frosty hue of arctic ice. ‘I’m looking for people who live without a fridge,’ I wrote. Dozens responded.

Most had not chosen a fridge-less life. They were forced into it by circumstances: renovation, moving out, a fault. One person had lost their house and moved into a security office on an industrial estate. Another had gone to work on an eco-farm, which simply didn’t have a fridge. Someone else had moved to their aunt’s whilst their studio was being renovated. One fridge was in the kitchen, working even, but, despite the makeshift duct tape, the door wouldn’t close; suddenly, it was possible to simply do without.

I looked at kitchen after kitchen, at the idle spaces therein, at the cracks, the shadows, the afterimages, the imperfections: fridges-turned-whiteboards, fridges-turned-cabinets, fridges with no discernible purpose; unplugged fridges, giving off the smells they once managed to absorb, dormant yet alert, with mustards and sauces rattling around on the shelves.

Their owners and users all said the same thing: surprisingly, they throw away a lot less food. They buy more often, for less. They cook less extravagantly. And leftovers – if any – are eaten the next day. Meat spoils easily, so they have given it up. And butter? They only eat it in winter – yes, the windowsill works great. They drink beer as soon as they buy it. They store stew – vegetable, of course – in the oven and eat the soup if it turns sour.

Scientists studying food waste know all too well that these tactics should not be taken as read. When asked to testify about what edible food they throw away, most people tend to obfuscate and deny their habits. But the link between the technology used to extend the shelf life of food and how much of it we throw away is a clear one; indeed, it is a hot topic for scientists who study ‘garbology’. The bigger the fridge, the longer the shopping list; the longer the shopping list, the greater the waste. We treat it as a space where time stops, a fortress inaccessible to the rest of the (micro)world. The door closes, the light goes out; the food – organic matter, a terrain of constant processes – becomes immortal.

Only, it doesn’t. The cold merely slows down cellular metabolism and numbs microorganisms, slowing down their spread. It doesn’t stop it. That’s what freezing does – and even ice can’t completely stop decomposition.

Image by Kit NG via Flickr

Top shelf, 10°C: mustards and jams

Experts estimate that there are nearly 1.4 billion domestic fridges and freezers in the world. Statistically, in Europe, a single refrigerator is shared by two people. However, artificial cold accompanies food not only in the final stage of its life in our homes but also throughout its journey. It allows us to deceive seeds into thinking it’s not yet time for germination, keeps brewing bacterial cultures in check, preventing them from growing too large, and inhibits the action of plant hormones responsible for fruit ripening or stimulating sugar metabolism in tubers. Refrigeration gives us an upper hand in our competition for nutrition fought with the rest of the natural world. The microscopic elements of this world aren’t invisible but provide us with proteins, carbohydrates and fats. Helping plant tissues maintain their firmness, low temperatures also make food more appealing visually. There’s a nice word for this: turgor. Without turgor, that lettuce sitting in your fridge would be in the bin.

Sometimes cold accompanies food on its final journey. If it is not sold within the allotted time and is written off as waste, it ends up in the cold, hidden behind an armoured door. The moment it is scooped up by a garbage truck is like a first breath of tropical air after leaving air-conditioning; it’s not long before natural processes get underway.

Any break in the chain of chill is – according to the modern approach to food distribution – an emergency. Food, suspended from maturing, suddenly gasps for air and starts to make up for lost time. An apple, kept in a cold warehouse for a year, from which virtually all oxygen has been pumped out, lingers in dormancy. A wisp of air brings it to life. It wants to ripen, to wrinkle, to give its seeds to the world. And this does not necessarily go hand in hand with its appeal as food.

Middle shelf, 4°C: ham (wrapped, of course)

In the sociology of poverty, several indices are used when trying to assess the extent of economically deprived communities. Not having a fridge – along with the absence of a telephone, colour TV, access to protein and engagement with leisure activities – is one of them.

Over 27,000 households in Poland live without the equipment that allows food to be cooled to 4°C – that’s as many as the entire number of residences in Gdańsk. Those going without do not consciously choose to live a fridge-free life. Often, they live without a kitchen, electricity or money; indeed, they may well live without any of these, just about getting by from one day to the next in buildings that can hardly be called dwellings.

Those who consciously choose to live without a fridge are a handful that fall within the statistical margin of error. Electing to go without an appliance so ubiquitous in homes that it would never occur to anyone to analyse it in terms of superfluity seems extreme. Or a bold act of self-awareness.

While the fridge may seem innocent, especially when compared with blood-stained smartphones made from minerals whose mining creates conflict, global-heating air conditioning, and clothes dryers, which use dirty energy to hasten a natural process, it isn’t. It clearly contributes to the Earth’s compromised environment. Its impact is tangible: the cubic decimetres of cooling agents released into the atmosphere, alongside the degrees Celsius that heat it up, can be calculated. Although F-gases or hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs) – the successors to CFCs – may not destroy the ozone layer when released into the atmosphere (whether by accident or via improper disposal), they cause several thousand times more damage than carbon dioxide.

Discussions about changing this situation are long running. In 2016 nearly two hundred countries signed an amendment to the Montreal Protocol in Kigali. According to the agreement, virtually the entire world must stop selling and servicing appliances cooled by F-gases by 2028, replacing them with organic refrigerants. Despite this, millions of F-gas fridges, coolers and freezers remain on the market. Evidence of their damaging potential is hidden in safety information panels. Each one, especially if not disposed of properly, can harm the climate.

The Drawdown report, published in 2017 and referred to in statements from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), was optimistic. Researchers of the study ranked the potential of one hundred selected efforts to curb climate change, from most to least effective. Improving cooling appliances – refrigerators and air conditioners – came first. According to the report, if we were able to prevent leaks when replacing refrigerants, we would save the atmosphere nearly 90 gigatons of carbon dioxide emissions. In third place, saving 70 gigatons, was the reduction of food waste: the two categories remaining in a strong, chilly embrace with one another.

Bottom shelves, between 7 and 10°C (adjustable humidity): lemons and lettuce, separate

Ever since the first settlers, humankind has tried to extend the shelf life of food. In doing so, people have taken advantage of nature’s helping hand. Ice was cut from frozen lakes in winter or transported from glaciers. Large blocks of ice cut in January could be kept year-round. All one had to do was transport them to ice houses dug underground and cover them with sawdust. Insulated goods would lie dormant until next winter, bringing delight to the residents of manors and palaces.

But the world’s hunger for cold storage was growing, and by the end of the nineteenth century it could not be satisfied by nature alone. Technology came to the rescue: by controlling the metabolism of food, mastery of the entire system of food production and distribution was at hand. Think of equipment symbolic of the Anthropocene era and the refrigerator certainly comes to mind.

The ability to control temperature is one of the core pillars of today’s globalized food production and distribution system. But it also has a huge impact on what goes onto – and comes off of – the dining room table. Without refrigeration, we would be eating shrivelled apples and potatoes dotted with sprouts in the pre-harvest season, and fresh dairy, meat and fish would still be occasional delicacies, only available to the privileged. Tropical fruits would disappear from general sale, their freshness currently suspended from the moment they are harvested until they appear on the shop floor. We would eat more modestly, probably in accordance with the natural crop cycle in our geographical zones; crops that grow nearby do not need to travel thousands of miles to reach our plates. Cold storage, or rather the way we use it, has not only widened choice but has also instilled in us the belief that we can have everything, here and now, at our fingertips. It is also one of the reasons why we have stopped viewing food as an extremely valuable resource whose shelf life can be extended by putting in the effort: drying, salting, curing, fermenting, preserving. Now, all we have to do is open the fridge door.

Freezer, -18°C: not just for ice cubes

The Warsaw Museum of Technology has the oldest Polish refrigerator, dating from 1969, in its collection. With a capacity of only 40 litres, the Polar L9, manufactured by Wrocławskie Zakłady Metalowe (Wroclaw Metal Works), has just enough space to chill a few bottles – nowadays, such a volume would, at most, serve a camping trip or minibar.

The Einstein refrigerator – as this type is called – was popular before condensing refrigerators came along. Only able to maintain a temperature of around 10°C, and go down to minus three in a freezer with enough capacity for a few chops, its performance was not particularly impressive. That said, it was relatively inexpensive and – unless it leaked – virtually indestructible. Butter, milk, cheese and leftovers from dinner were stored there. It can still be found working in some homes, and on sale online for around 200 Polish złoty (just over €45).

Today, the average fridge bought in Europe has a capacity of around 200 litres – still quite a lot less than on the other side of the Atlantic. And it is its size, especially its depth, which makes food, stuffed under the back panel, disappear from view. A large refrigerator is well-equipped for waste; it brims with freshly bought groceries and leftover lunches, merely delaying the inevitable execution of their death sentence after being swept off the plate. The modern-day refrigerator is like a repository of remorse, a sarcophagus illuminated by an arctic hue; the emotions that come with throwing away food deposited within – shame, embarrassment, anger, regret – quickly cool off. They decay, just like food. After all, it’s far easier to tip soup that’s ‘gone bad’ down the sink than it is fresh soup, still steaming, straight from the saucepan. One may think: oh well, it’s gone off, there’s nothing I can do about it.

Refrigerators, by extending the lifespan of fresh food, provide us with a deal measured in time, which must be swiftly repaid when they refuse to cooperate. If refrigeration is ever interrupted, at home it’s not too disastrous. Everywhere else, however, the procedure is crystal clear: food must be thrown away.

When the industrial freezers at one of Poland’s food chains, located in the basement of a building dating back to the 1950s, went down a few years ago, some of what was doomed to thaw went to the staff. Even after eating melting cream cakes all day, they were unable to save it all, however; the wheelie bins filled up that day.

Image by nicotitto via Unsplash

Drawer (set to chill mode), -1°C : fish and meat

In 2017 the World Food Summit in Copenhagen debated how to reduce food waste. One of the many ideas raised came from the director of a multinational food company. ‘The solution, ladies and gentleman,’ he said, ‘is predictability’ – consumer behaviour being pinned down all the more. Call restaurants to tell them what you are going to eat. Let shops know what you are going to buy. Smart fridges will help with this: upon entering a shop, they will scan their interior using cameras, send you a shopping list and suggest that you do something about that cauliflower stuffed in the bottom drawer. ‘Hey, Marta, fancy some cauliflower soup today? Please eat me, Marta, because if you don’t, I’ll write about it on your profile and you’ll be embarrassed.’

A cool ‘home hub’ connected to the Internet – the marketing buzzword used by manufacturers for smart fridges – could make throwing away food less intimate, and therefore less likely. The price paid for this will be, as usual, information about our daily lives: what we buy, eat and throw away. Those who gain access to this knowledge will, no doubt, be delighted.

*

We managed without a fridge for several weeks. Eventually, we bought a new one: a free-standing fridge of average size by European standards, only without the drawers that keep vegetables in a state of delicious turgor (a pity, I know). Neither does it have an ice maker, an in-built touch screen, or any kind of surveillance apparatus. It’s filled with a refrigerant that, theoretically, has no greenhouse potential but is already beginning to gurgle alarmingly.

The author wishes to thank Zaslaw Adamaszek from the Museum of Technology in Warsaw for an informative talk on various aspects of mankind’s taming of the cold.

Translated by Stephen Gamage | Voxeurop