Photography: Freezing Moments, Creating Memories

Photography, often called the "art of freezing time," captures life in its raw, unfiltered form. With a single click, a fleeting moment becomes eternal a breathtaking sunset, a child's innocent smile, or an intimate gesture preserved forever. More than a technical process, photography is a visual narrative that invites the viewer into the artist’s world.

Emotional Resonance Through the Lens

A photograph has the power to evoke deep emotions, provoke thoughts, and tell compelling stories. Iconic photographs throughout history images of triumph, grief, hope, and struggle carry messages that transcend words. These visual stories not only connect us with past events but also resonate on a deeply personal level, uniting viewers regardless of language or cultural background.

Technology and the Democratization of Photography

The evolution of technology has made photography more accessible than ever. Smartphones equipped with advanced cameras empower everyone to become storytellers, capturing and sharing their perspectives instantly. Social media platforms amplify this democratization, giving diverse voices a global stage.

However, with accessibility comes the challenge of authenticity. As filters and editing tools redefine reality, the line between art and manipulation blurs. In this age of digital photography, the true artistry lies in the intention behind the lens the ability to tell a story, provoke emotion, and inspire reflection.

Painting: The Language of the Imagination

While photography captures the external world, painting is a portal into the imagination. With a brush in hand, artists create visual symphonies on canvas, blending colors, shapes, and textures into works that evoke emotion and invite interpretation. Unlike photography’s immediacy, painting often requires deliberate thought, offering a reflective process that connects deeply with both artist and viewer.

The Emotional and Therapeutic Power of Painting

Painting transcends mere visual appeal; it offers profound emotional and therapeutic benefits. The process of painting can be meditative, providing a sense of calm and focus. For many, it serves as a way to process emotions, reduce stress, and heal from personal struggles. The blank canvas becomes a safe space for self-expression, where the artist can explore and confront their inner world.

Abstraction and Freedom

One of painting’s most distinctive qualities is its ability to convey abstraction. While photography is often tied to reality, painting liberates the artist from these constraints, allowing for abstract or surreal interpretations. This freedom enables viewers to engage with the artwork in unique and personal ways, finding meanings that may differ from the artist’s intent yet resonate deeply.

The Intersection of Art Forms

Though distinct in nature, photography and painting share a symbiotic relationship. Both mediums offer ways to explore the human experience, often influencing and inspiring one another. For example, photographers may incorporate painterly techniques like dramatic lighting or compositional elements to enhance their work, while painters may draw from photographic references to inform their creations.

The blending of these art forms reflects the diversity of human creativity. It also underscores the idea that artistic expression, regardless of medium, serves as a universal language one that fosters connection, inspires change, and bridges cultural divides.

Why Creative Expression Matters

Art, in all its forms, is an essential part of the human experience. It is not merely a pastime but a way to process, connect, and transform. In a fast-paced world, creative expression allows us to pause, reflect, and rediscover the beauty in everyday life.

Whether you choose to pick up a camera, paintbrush, or any other tool of expression, the act of creating is a gift not just for the artist but for all who experience the result. Embrace the art of seeing, and let it inspire you to share your story with the world.

Click on the link below to get more tips on lifestyle:

https://fhslifestylemagazine.com/

Start your wellness journey to better health today! Join our upcoming events

]]>

It is a way of remembering important people and events in the history of Africans in diaspora.

Carter Godwin Woodson is the founder and originator of the black history month he has been called the “father of black history”. He was an American historian, author, journalist., and the founder of the Association for the study of African American Life and History (ASALH). He was one of the first scholars to study the history of the African diaspora.

In February 1926, he launched the celebration of “Negro History Week”, the precursor of Black History Month. He was a strong force to the movement of Afrocentrism due to how he always placed the people of African decent at the center of the study of history and the human experience. He was born in Virginia and was a son of a former slave.

The black history month is celebrated in February in the United states and Canada, where it has received official recognition from governments, and has recently been celebrated in Ireland and the United Kingdom where it is observed in October.

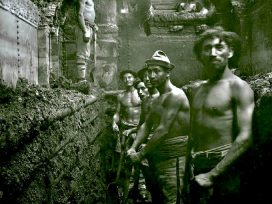

Since it gained recognition as an official heritage celebration, black history month has been assigned a theme for each year of its celebration. This year’s theme is “Africans Americans and labor”, a theme intended to encompass all the ways black people have experienced hard labor historically and currently.

In time past the themes have been “Black Resistance”, which focuses on honoring the heroes whose continuous resistance led to justice and freedom for Black Americans.

The celebration literally begins on the 1st of February and finishes on the last day of the month.

“we have so far mopped about 300 of these boys from the streets and taken them in to a camp provided for their rehabilitation. Their continued living on the streets is a huge social and security threat because they are potential criminal recruits.”

“They are a ticking time bomb that needs to be urgently defused with tact and care,” said Sufi.

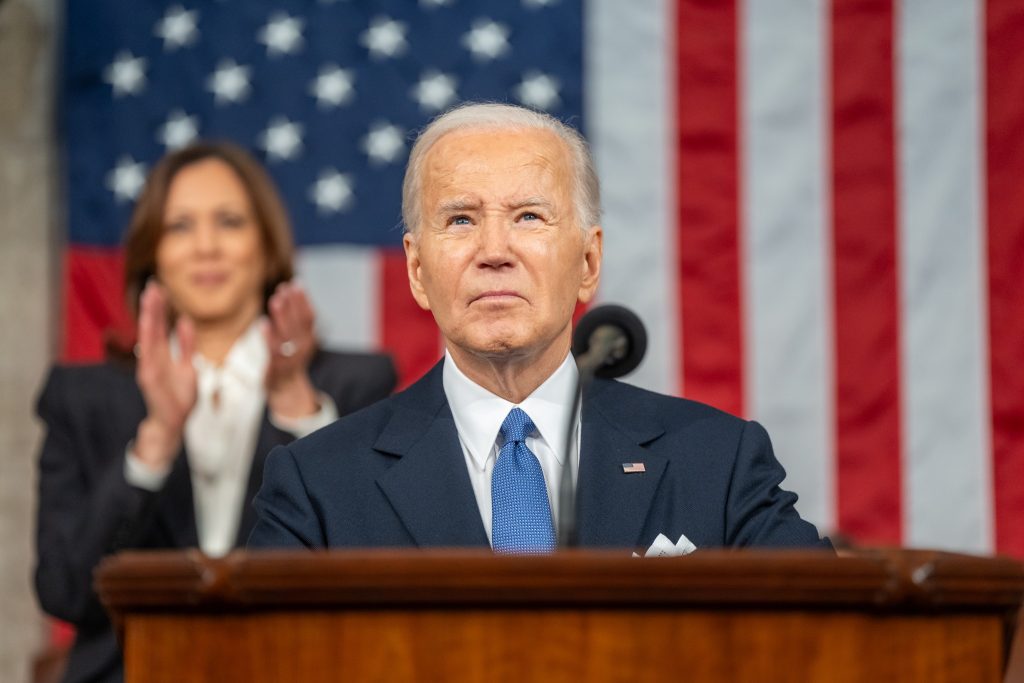

1. Policy Positions and Platform

The heart of any candidate’s campaign is their stance on key issues. It’s essential to dig into the details of each candidate’s platform. What are their plans for healthcare, education, the economy, and climate change? Do they have a clear and actionable strategy, or are their promises vague and noncommittal? Aligning a candidate’s policies with your own values and priorities is the first step in making an informed decision. Take the time to compare their platforms—who is offering the solutions that resonate with you?

2. Leadership and Experience

Experience in governance can be a strong indicator of a candidate’s ability to lead effectively. Consider each candidate’s track record—have they served in public office before? What have they accomplished? Leadership is not just about holding office; it’s about demonstrating the ability to navigate complex issues, make tough decisions, and manage crises. Look at their history of leadership. Do they have the experience needed to steer the country through challenging times?

3. Integrity and Character

A president’s character is often tested in the most public and high-pressure situations. Integrity, honesty, and moral fortitude are crucial qualities for any leader. Reflect on each candidate’s past actions, how they’ve handled scandals or controversies, and whether they’ve remained consistent in their principles. Do they show transparency and accountability? Trust in a candidate’s character is fundamental, as it directly impacts their decision-making and how they represent the nation on the global stage.

4. Vision for the Future

Beyond policies, a candidate’s vision for the future is a powerful element of their campaign. What kind of America do they aspire to create? Are they forward-thinking, with plans that address both immediate concerns and long-term challenges? A compelling vision can unify and inspire voters, offering hope for progress and change. Consider whether their vision aligns with your own hopes for the country’s future.

5. Approach to Bipartisanship

In a nation as diverse as the United States, the ability to work across the aisle is essential. With the country deeply polarized, a president who can foster bipartisan cooperation is more likely to achieve meaningful progress. Evaluate each candidate’s history with bipartisanship. Have they successfully worked with the opposing party to pass legislation? Are they willing to compromise to achieve broader goals? A candidate’s approach to bipartisanship can reveal much about their potential effectiveness in office.

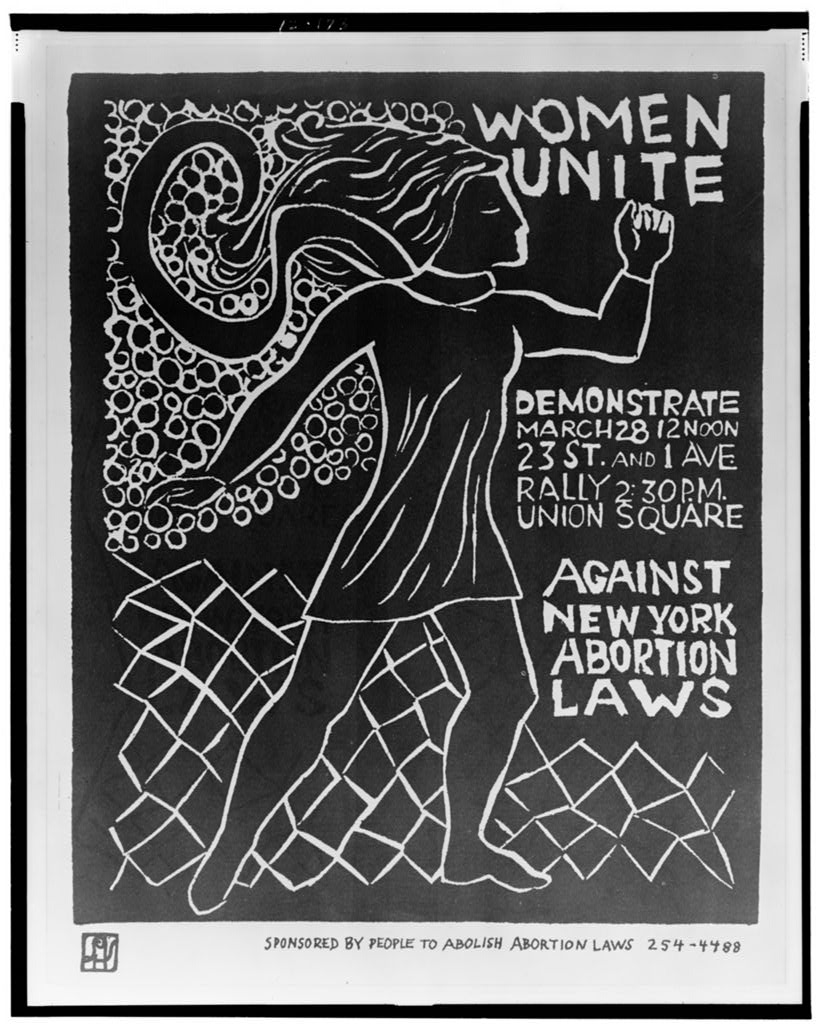

6. Stance on Key Social Issues

Social issues remain at the forefront of the national conversation. Issues like racial justice, gender equality, LGBTQ+ rights, and immigration policy will undoubtedly influence the 2024 election. Consider each candidate’s stance on these critical issues. How will their policies impact marginalized communities? Are they advocating for inclusivity, equity, and justice? The way a candidate addresses social issues can be a reflection of their broader values and their commitment to protecting the rights of all Americans.

7. Economic Plan and Impact

The state of the economy is always a significant concern for voters. Assessing a candidate’s economic plan is vital. How do they propose to stimulate economic growth, create jobs, and manage the national debt? Think about how their policies will impact not only the national economy but also your personal financial situation. Will their economic policies benefit the middle class, or are they more geared toward the wealthiest Americans? The right economic plan should aim to lift everyone and create opportunities for all.

8. Environmental and Climate Policies

Climate change is one of the most pressing global issues of our time. The next president’s approach to environmental policy will have long-lasting effects, not just domestically, but internationally. Review each candidate’s plans to combat climate change. Are they committed to reducing carbon emissions, investing in renewable energy, and protecting natural resources? A candidate’s stance on environmental issues can indicate their commitment to science and their willingness to take bold action on global challenges.

9. Foreign Policy and National Security

The president of the United States plays a critical role in shaping the country’s foreign relations and ensuring national security. Examine the candidates’ foreign policy experience and their approach to international issues. Do they have a clear strategy for maintaining and strengthening global alliances? How do they plan to address emerging threats like cyber warfare, terrorism, and nuclear proliferation? A candidate’s foreign policy views can provide insight into how they will position the United States on the world stage and protect its interests.

10. Electability and Public Support

While it’s important to align with a candidate’s policies and values, electability is also a practical consideration. A candidate must be able to garner enough support to win not just their party’s nomination, but also the general election. Consider factors such as their ability to connect with voters, build a broad coalition, and secure key swing states. Assess their campaign infrastructure, fundraising efforts, and overall public support. Electability isn’t just about popularity; it’s about the strategic elements that will ultimately lead to victory in November.

Choosing the next president of the United States is a profound responsibility, and it’s one that requires careful consideration of multiple factors. From policy positions and leadership experience to character and electability, each element plays a crucial role in determining the best candidate for the job. As you prepare to vote in the 2024 presidential election, take the time to research, reflect, and engage with the issues that matter most to you. By considering these ten factors, you’ll be better equipped to make a choice that aligns with your values and the future you envision for the country. Remember, your vote is your voice—use it wisely to help shape the path forward for America.

]]>However, the COVID-19 pandemic has significantly impacted my business, which serves as the backbone of these humanitarian efforts. The decline in sales has hindered my ability to sustain and expand my initiatives. Now, more than ever, the world needs healing and cleansing. As we navigate the post-COVID era, the importance of natural remedies and immune support cannot be overstated.

I am reaching out to you for support in raising $125.,000 to enhance and expand the State to States Herbal Healing Campaign.

With these funds, I aim to:

1. Purchase an RV Truck: This will serve as a mobile clinic, enabling us to travel from state to state, bringing herbal healing to underserved communities.

2. Acquire Herbs and Equipment: Essential supplies for creating and distributing herbal remedies.

3. Conduct Free Healing Sessions: Provide free herbal treatments to the less privileged, helping them improve their health naturally.

4. Host Seminars and Workshops: Educate communities on the benefits of herbal remedies and how to use them to treat various illnesses.

The Impact of Your Support

Your generous contribution will enable me to reach more people in need, offering them hope and healing through natural means. The mobile clinic will allow me to:

- Provide Free Herbal Remedies: Distribute herbal treatments to individuals who cannot afford conventional medicine.

- Offer Free Educational Workshops: Empower people with knowledge about natural health solutions, boosting their ability to manage their health.

- Conduct Immune-Boosting Programs: Help individuals with low immunity build stronger defenses against diseases, reducing their vulnerability to illnesses.

Why Herbal Healing?

Herbal remedies have been used for centuries to treat various ailments and maintain overall health. They are cost-effective, accessible, and often come with fewer side effects than conventional pharmaceuticals. In a world still reeling from the effects of the pandemic, herbal healing offers a natural, sustainable way to support our bodies and minds.

How You Can Help

I invite you to join us in this mission of love and healing. Your donation will make a significant difference in the lives of many, providing them with the tools and knowledge they need to lead healthier lives. Together, we can honor Latorrie’s memory and create a legacy of compassion and wellness.

To contribute, please visit our campaign page https://gofund.me/e0c1f1cb or order my book herbal bundles containing four useful e-books for just $24.99. https://finestherbalshop.com/products/herbal-book-bundle .Every dollar brings me closer to my goal and allows me to spread hope and healing across the nation.

Thank you for your support and for believing in the power of natural healing. Together, we can make a difference.

Sincerely,

]]>Turning 60 is such a great blessing and it leaves me in a state of awe and gratitude as I reflect on my life over the years. My years have been multiplied 6 by 10 times and so for that blessing I will share 6 proclamations of gratitude as I celebrate life on this day.

1. I am grateful that the Heavenly Father has called me into such a ministry of holistic and herbal medicine. The gift he has endowed upon me has not only been a blessing to me and my family but to countless others.

2. I am grateful for the many clients whom I have been blessed to work with, and have helped along their journey of healing and restoration. Being able to minister to clients struggling with various health issues such as diabetes, heart conditions, fertility issues and more has been a fulfillment of the calling placed on my life.

3. I am grateful for the support of my loved ones who continue to stand by me, encourage me, uplift me and pray for me.

4. I am so grateful for the Finest Herbal Shop (FHS) which has become a central hub for people all over the world to find resources that help guide them on a healthy lifestyle journey. FHS provides connections to various classes and trainings to educate and empower people to take ownership of their of their health. It has truly become a haven for many looking for natural healing remedies.

5. I am grateful and honored to have been chosen to receive the Presidential lifestyle achievement award for my humanitarian efforts by the African and Caribbean International Leadership Conference. This is such a great accomplishment to know that my influence isn’t localized but rather is blessing many individuals around the world.

And lastly…

6. I am grateful for my renewed commitment and dedication to continually use this gift to help heal the world one client at a time. I am committed to the belief that change is indeed possible through educating, empowering and elevating others to a greater level of understanding on the power of herbs and their natural healing elements. 60 years down and I am committed and purposed to continue walking this path for all my days.

If you are wondering how to start your own personal holistic journey of healing and restoration, I am here for you! Whatever concerns you may have in regard to your health ranging from diseases such as diabetes, hypertension or infertility to skin care or hormonal imbalances, I can help you. Feel free to reach out to me and let’s talk!!

Today I am forever grateful!

Happy 60th birthday to me!!!

Click Here to get a copy of my birthday giveaway.

Show your love and support for my birthday day by subscribing to my YouTube channel

Click Here to subscribe to my YouTube Channel

]]>On 20 March, at the opening ceremony for the annual Leipzig Book Fair, the 2024 Leipzig Book Prize for European Understanding was awarded to New School philosopher Omri Boehm for his book Radikaler Universalismus (Radical Universalism) (Propyläen Verlag, 2022). During a keynote address that preceded Boehm’s acceptance speech, German Chancellor Olaf Scholz was interrupted repeatedly by shouting from several demonstrators accusing the German government of complicity with Israeli genocide in the Gaza strip. ‘The power of the word,’ Scholz responded, ‘brings us all together here in Leipzig – not shouting.’

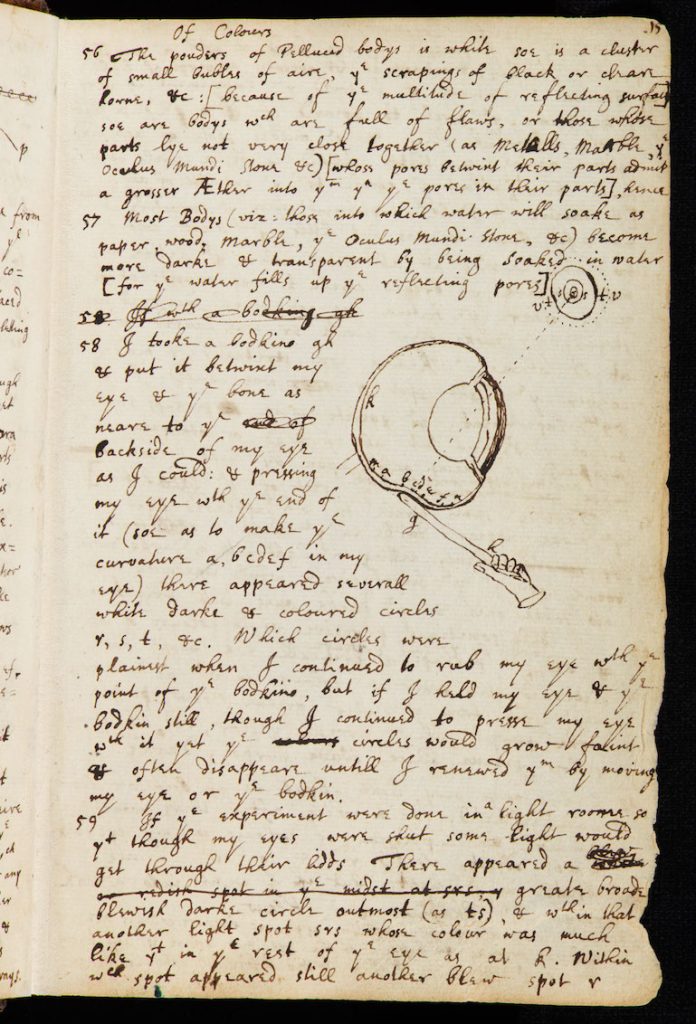

At the start of his formal speech, Boehm reminds his audience of the public conversations about the meaning of Enlightenment among intellectuals like Immanuel Kant and Moses Mendelssohn in the 1780s. He also discusses the contemporary friendship between the Jewish philosopher Mendelssohn and the Protestant playwright Gotthold Ephraim Lessing. Their friendship was memorialized in Lessing’s play Nathan the Wise and its famous ring parable, which suggests that we judge Jews, Christians and Muslims not by the differing religions they profess but according to their conduct and the similar virtues that make them pleasing to God.

Public Seminar

‘Jerusalem sky’. Image: Bon Adrien / Source: Wikimedia Commons

***

I was going to read a rather long and philosophical acceptance speech, but, after the disruption we saw earlier this evening, it must become somewhat longer. I’d like to say a word about what happened earlier on.

Speech and public discussion are the vehicles of reason and universalism. But that open speech, reason, and universalism are the answer to the burning injustices of the world and our time cannot be taken for granted. Sometimes – often, even – they serve as a mask that helps preserve an unjust status quo that ought to be challenged. The protesters tonight made an awful mistake. But they were trying to tell us something about open speech – and they were trying to tell us that by their disruption of a speech.

It was and is necessary to stop their disruption. But it is insufficient. We still have to rise to the challenge of showing that speech and open discussion can facilitate necessary, urgent changes – and not just block them. My book Radical Universalism is about that very problem. Defending universalism must go through listening to what these protestors tonight had to tell us. The answer that the book offers is, however, not the same as theirs, but the opposite.

On the night of 31 December 1785, an old Jewish man left his home in Berlin to rush a book manuscript for publication. It was ready the evening before, but it was Friday, and he had to wait for the end of the Shabbat. His wife warned him. It was too cold. He was too frail to leave the house. Four days later, he died of complications of a cold he caught that night. The old man was Moses Mendelssohn, the towering figure of the German and the Jewish Enlightenment. The book that was so urgent to him was titled An die Freunde Lessings (‘To Lessing’s Friends’).

The friendship between Mendelssohn and Lessing is not only the origin of the tragic ‘Jewish- German symbiosis’ – Lessing famously modeled Nathan der Weise after the character of his Jewish friend – but also, not less significantly, it was the model of Christian-Jewish-Muslim understanding: Nathan’s well-known Ring Parable has three rings, not two. This ideal of understanding is a proud European one, but Lessing had good reasons to place its origins outside of the continent – the drama takes place in Jerusalem. Alongside Kant’s well-known essay, Lessing’s Nathan is probably the boldest answer we know to the question: What is enlightenment? Was ist Aufklärung?

For Kant, enlightenment is humanity expressed through the freedom to think for oneself. For Lessing, it is humanity expressed through the freedom to form friendships. At a few crucial junctures in the play, Nathan proclaims: Kein Mensch muss müssen (‘No one must must’). It is only in light of this assertion of freedom that the play’s familiar motto comes to shine, as Nathan stresses in all directions: Wir müssen, müssen Freunde sein! (‘We must, we must be friends!’) But what is the relation between Kant’s enlightenment and Lessing’s, between the ideal of thinking for oneself and that of friendship?

In 1959, Hannah Arendt received the Lessing Prize from the City of Hamburg. Her acceptance speech, Von der Menschlichkeit in finsteren Zeiten (‘On humanity in dark times’), could just as well have been titled ‘To Lessing’s friends’. If bringing things into the sun – into the light of public discourse – normally illuminates thinking, a dark time for Arendt is one in which ‘the light of the public obscures everything’ (Das Licht der Öffentlichkeit verdunkelt). In dark times, public speech, the main pillar of enlightenment, betrays; trust in a shared human life lies shattered. But, says Arendt, ‘Even in the darkest of times we have the right to expect some illumination,’ which comes from the ‘flickering light’ that, under almost ‘all circumstances,’ some unique men and women ‘shed over the time-span that was given them on earth.’

At such dark moments, we search for alternative pillars. One alternative is brotherhood, fraternité – quite literally the unconditional solidarity that forms among persecuted groups through attachment to their own identity. Arendt doesn’t doubt that such bonding of the persecuted is often necessary and produces true greatness, but she insists that, by reducing humanity to the identity of the ‘persecuted and the enslaved’, it constitutes a retreat into privacy. A logic of universal brotherhood depends on what we have in common with others, not on difference from them. Moreover, the solidarity of the persecuted cannot extend beyond the persecuted group – to those who are in position to take universal responsibility, in love of the world. That’s the origin of Arendt’s familiar critique of identity politics in general and the politics of her own Jewish identity, Zionism.

A second alternative in dark times is truth. Specifically, the ‘self-evident’ truths that can be known by all, regardless of belonging – thereby serving as a pillar of shared existence. Yet Arendt knows well that falling back on truth in dark times has become questionable, since self-evident truths in modern societies have been pushed to the side. ‘We need only look around to see that we are standing in the midst of a veritable rubble heap … [that] public order is based on people holding as self-evident precisely those “best-known truths” which, secretly scarcely anyone still believes in.’

I think that Arendt was right about the demise of truths considered ‘self-evident’, perhaps with the only difference that, in our times, the fact that scarcely anyone believes the ‘best-known truths’ is no longer much of secret. That hardly anyone accepts the proposition, ‘We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal’ is almost too obvious; about the truth of the claim Die Würde des Menschen ist unantasbar (‘Human dignity is inviolable’) people are still willing to dissemble.

The core idea of my book Radical Universalism was to warn that such post-humanism is not just a theoretical nuance, not just noise that’s generated by the petty scandals of cancel culture, but much more dangerous; and to try to draw on Kant in order to show that it is possible – in theory and in practice – to rehabilitate our relation to such truths, as opposed to identity or a narrow brotherhood of the oppressed. The book’s goal was to insist on Kant’s idea of humanity as a moral rather than a biological category, thereby stemming the tide of the dark post-humanism that has infected the identitarian Left, the identitarian Right and, no less importantly, the identitarian center, whose alleged opposition to identity too often amounts to a narrow brotherhood of the privileged.

But Arendt doesn’t go there. She goes with Lessing, not with Kant, namely with his ideal of friendship as the alternative to both identity and truth: more specifically, the ideal of friendship that Lessing had rehabilitated from Aristotle, as a public affair, rather than a private, personal matter as we have come to think of it in modern societies. The main characteristic of such friendship is (allegedly) its opposition to truth. In the name of friendship and Menschlichkeit (humanity), truth must be put aside. To quote from Arendt: ‘The dramatic tension of [Nathan der Weise] lies solely in the conflict that arises between friendship and humanity with truth … Nathan’s wisdom consists solely in his readiness to sacrifice truth to friendship.’ In this sacrifice lies not just Nathan’s wisdom, but his ideal of enlightenment. Indeed, for some people the tension Arendt alleged to exist between cold truth and warm friendship has become almost axiomatic.

But I think Arendt’s interpretation of friendship is false. There’s no tension between what I call ‘radical universalism’, the Kantian Enlightenment, and the idea of friendship. On the contrary.

To see why, it’s worth returning to Aristotle. One of his most familiar statements is Amicus Plato, sed magis amica veritas (‘Plato is my friend, but truth is a better friend’). At first glance, it seems the philosopher of friendship has chosen truth over friendship. But on closer examination of the text, Aristotle doesn’t prefer truth to friendship; for when he chooses truth, it is precisely because truth is a better friend. His statement has to be understood in light of Aristotle’s account of friendship. For Aristotle, the ideal of genuine friendship can only be achieved in the relation between virtuous individuals, and virtuous individuals cannot assume that a statement of truth contradicting the other can constitute personal harm – indeed, just the contrary. Therefore, when Aristotle is out to undermine Plato’s theory of the forms with the statement Amicus Plato, sed magis amica veritas, he says this because he must, he must be Plato’s friend.

And Kant? It is striking that whereas the Aristotelian interest in friendship almost disappeared in subsequent philosophy, it was Kant, the philosopher of autonomy, who rediscovered it as a philosophical topic and ventured to explain our ‘duty to friendship’ as a ‘schema’ – the Kantian technical term – of the categorical imperative, that is, of treating humans as ends rather than means. As such a schema, the idea of friendship serves as the bridge, a necessary one, between the abstract notion that stands at the height of Kant’s whole philosophy – treating humans as ends – and concrete experience. If you want to generate an image showing what treating humans as mere means amounts to, think of slavery. For an image of treating them as ends, think of friendship.

Now recall that for Kant, enlightenment is thinking for oneself. But, crucially, thinking for oneself isn’t something that can be done alone. Kant argues that we would not be able to think very ‘much’ or even ‘correctly’ if we could not think together ‘with others’ with whom we ‘communicate’. The big Kantian discovery was that Öffentlichkeit (that is, the public sphere) is necessary to enlightenment and reason. Yet Kant is aware that under some circumstances we cannot but be ‘constrained’, holding back significant parts of our judgments in public. We’d like to discuss our positions about ‘government, religion and so forth’ but cannot risk sharing them openly.

But if we have a friend we can trust, we can ‘open’ (eröffnen) ourselves to them and thereby are ‘not completely alone’ with our ‘thoughts, as in a prison’. The word eröffnen is at the very heart of the idea of friendship. In dark times, when the Öffentlichkeit and the light of publicity necessary to thinking for oneself dims, friendship allows us to continue to open – eröffnen – our thinking, preserving the transformative power, even the revolutionary potential, of thinking for oneself.

C.S. Lewis once wrote that every friendship is ‘a sort of secession, even a rebellion … a pocket of potential resistance.’ Kant would agree.

Looking at the Kibbutzim on Gaza’s border on October 7 – as complete families were slaughtered, children murdered in front of their parents, women systematically raped, and hundreds of hostages taken – and then witnessing the moral bankruptcy of those alleged radicals who call this ‘armed resistance’; looking at the flattening of Gaza, the killing of tens of thousands of women and children, the catastrophic starvation – and then witnessing alleged liberal theorists delegitimize for months a humanitarian ceasefire in the name of ‘self-defence’: in this shouting match between the proponents of the ‘armed resistance’ doctrine and the ‘self-defence’ theory we see what a dark time looks like – when the light of the public obscures more than it reveals.

Perhaps at this moment, speaking of friendship between Israelis and Palestinians could seem too rosy, naïve, or utopian. Even worse, it could seem grotesque.

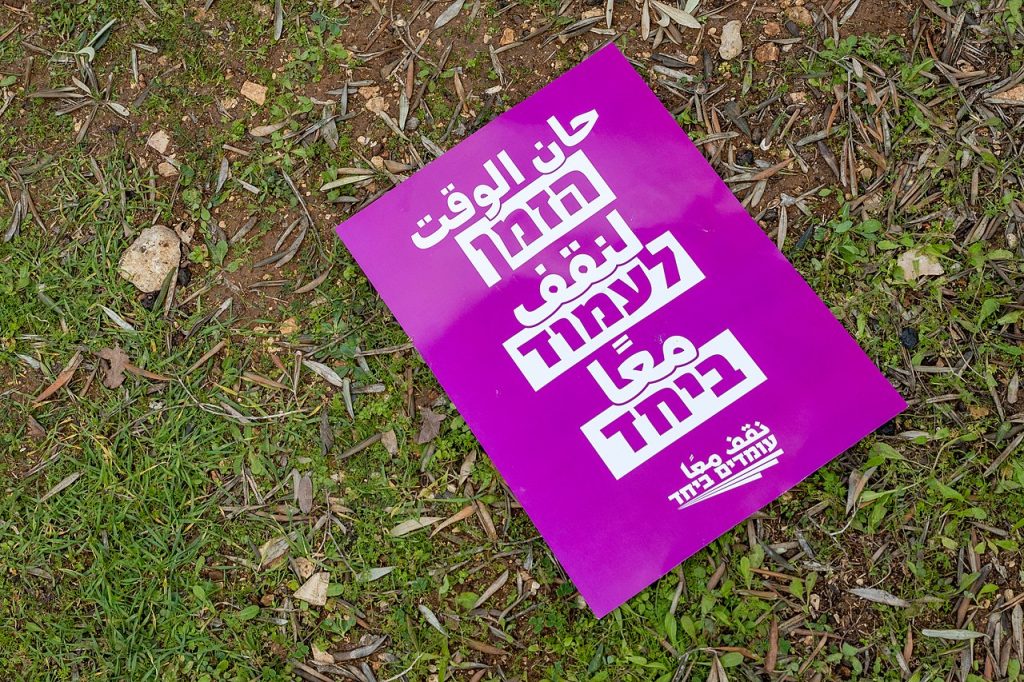

But no. Jewish-Palestinian friendships do exist; and where they do, the difficult demands that they pose offer light – and perhaps the only true source of enlightened resistance.

Israeli and Palestinian friends could not pretend that what happened on October 7 happened in a vacuum, just as much as they knew that speaking about this mass murder as ‘armed resistance’ was humiliating, first and foremost to proud Palestinians who rightly demand freedom. My Palestinian friends know that whoever calls what my country is doing in Gaza ‘self-defence’ humiliates my identity to the core. Israeli and Palestinian friends can talk to each other, and in public, about the catastrophe, and about the catastrophic failures of our brothers and sisters, knowing that if, after we speak, we are unable to look our friends in the face, we will also be unable to look in the mirror. Friendship was always the test that protected us from the catastrophic failures of brotherhood and the grotesque abuse of abstract ideas about armed resistance and self-defence.

In 2010, Ahmad Tibi, a Palestinian Israeli member of Knesset, gave a Holocaust memorial speech: ‘This is the place and the time to cry out the cries of all of those who [are struggling] to unburden themselves from the scenes of death and horror.’ And he continued: ‘On this day, one must shed all political identities’ and ‘wear one robe only: the robe of humanity.’ This robe of humanity isn’t abstract humanism, but humanism expressed as the Freundschaftserklärung (the declaration of friendship) of a Palestinian representative who shares with Jews, as Tibi said, ‘the same land and the same country.’ This Freundschaftserklärung was uncompromising, even radical, and posed Israelis a provocation, because friendship with Jews requires equality. But no one can doubt in good faith that the man who gave that speech, and people represented by him, had any patience with the violent nonsense of alleged radicals who spoke of October 7 as ‘armed resistance’.

On the Jewish side, I cannot but think of the words of Amos Oz, uttered in a completely different time: ‘The idea of expelling and driving out the Palestinians, deceitfully called here a “transfer” … we must rise and say simply and sharply: it is an impossible idea. We will not let you do that … Israel’s Right must know that there are acts that, if attempted, will cause the split of the state.’

This was said decades before the people that Oz addresses – the religious Right – had become a major force in the Israeli government. That’s why his words only make sense if they are repeated today. His use of ‘we’ and ‘you’ in this paragraph means everything: the acts that ‘we’ will not let ‘you’ do are the ones that fracture Jewish brotherhood. If we don’t repeat Oz’s statement as we look at Gaza today, knowing that the idea of transfer is anything but impossible, we will not be able to look our Palestinian friends in the face.

And what about Jewish-German friendship? Where it exists – and in some places, it does – it is a true wonder, one that is very personally dear to my heart. But this wonder now has to be protected from debasement. No Jewish-German friendship could exist if it cannot, in our dark times, have room to acknowledge the difficult truths that must be stated publicly in the name of Jewish-Palestinian friendship. Any other notion would humiliate Mendelssohn and Lessing’s model: Nathan’s ring parable has three rings, not two, and there will be no less than three rings for us.

Truth does not have to be put to the side in this dark time. For as Kant knew as well as Lessing, we ought, we ought to stay friends.

]]>Since the collapse of socialism, demographic change has emerged as one of the biggest Rashomons of contemporary societies, especially in Central and Eastern Europe (CEE). Understood as a palpable concern by some and dismissed as a political construct by others, it is becoming increasingly prominent in public discourse. In a region with contested yet increasingly liberal social norms, including declining childbearing preferences, conservative governments from Budapest to Warsaw and Belgrade have sought to turn back the societal tide encouraging people to have more children. Financial assistance for parents, especially when coupled with abortion restrictions, have attracted a considerable liberal backlash. But should pronatalism be seen as a conservative cause? Or could raising the birth rate – currently at an all-time low in the region and lower than in most of the continent – bring palpable benefits for states and societies?

Demographers point out that low fertility, which together with increasing life expectancy results in ageing populations, raises a wide range of questions about the future sustainability of pensions, healthcare and overall living standards. Of course, concluding that these challenges can be best addressed by encouraging more births is a leap of faith. Babies increase the share of dependents in a population before decreasing it decades into the future.

Other solutions are more immediate but less feasible or popular. Immigration, especially from outside of Europe, has been shunned by the same pronatalist governments allegedly concerned about unfavorable demographics. Adaptation, for instance by lengthening the amount of time spent in work, tends to draw massive popular opposition. Automation carries electoral risks of its own and can prove challenging to implement even if the political will is found. Free from such obstacles, pronatalism has become the name of the game.

One child fewer than preferred

Even the biggest critics of CEE pronatalism could not dispute the scale and speed of the region’s fertility decline. Despite varied economic and political landscapes, CEE countries share strikingly similar fertility figures. From Budapest to Vladivostok, birthrates hover close to the EU average of 1.6 children per woman, with notable exceptions being Ukraine and Poland, where the figures dip even lower.

Beneath this overarching narrative of decline, however, lies a complex tapestry of desires and realities. Contrary to the prevailing notion of a burgeoning ‘childfree’ society, opinion surveys suggest a persistent CEE preference for larger families: most individuals aspire to the traditional two-child ideal. However, they find themselves constrained by a multitude of factors, ranging from health-related issues exacerbated by lifestyle choices and delayed parenthood to overestimations of the efficacy of reproductive technologies.

Cultural trends also exert a significant influence. Traditional divisions of labor within the home, which assign the bulk of domestic and caregiving responsibilities to women, are increasingly at odds with contemporary social norms. Faced with the ‘double burden’ of work and care, more women are opting for employment over children. Obsolete understandings of family life paradoxically keep birth rates low, much to the chagrin of traditionalists and many progressives alike, as evidenced by the persisting average preference of about two and a half children per woman.

Children’s hands as puppets. Image by jacquelinetinney via Flickr

Voluntary or not, the otherwise European-wide trend of low birth rates poses a more pressing challenge to CEE. Unlike population trends in most of Western Europe, and to a large extent because of Western Europe, net emigration characterizes CEE’s demography. Italy is a key example of a Western European country also with a low birth rate, ageing population and high level of emigration, especially of young people. While migration data tend to be patchy, it is evident that the balance between births and deaths, even though negative in most places in the region, is insufficient to explain key demographic changes. The EU’s ‘big bang’ enlargement into CEE in 2004, while enormously beneficial for the region, has also reduced its populations, as millions of people opted for an immediately higher standard of life in Western Europe as opposed to the near-assured yet incremental prospect of progress at home. Contrary to what pro-EU policymakers would like to hear, the exacerbating effects of EU accession on brain drain do not bode well for the Western Balkans, further strengthening the case for pronatalist policy.

Three or four children, no more, no less

At first glance, pronatalism seems equally widespread on both sides of the former Iron Curtain. The biggest star at the 2023 Budapest Demographic Summit A biannual international gathering of pronatalist policymakers, activists and church officials hosted by Hungary’s prime minister, Viktor Orbán. was not an East European politician but Italy’s prime minister, Giorgia Meloni, who has taken measures against a declared population crisis in her country. A similar pan-continental picture emerges from the official stances of European governments regarding their desired fertility levels: in 2019 81% said they wanted births to go up, with no major geographical differences.

However, if one scratches beyond the surface of self-declarations, it appears that, apart from Meloni, it is mainly CEE policymakers who are putting their money where their mouth is. While the regional pioneer of pronatalist policy was Russia, which unveiled its Maternity Capital programme as early as 2007, it has since been surpassed – in both financial ambition and political saliency – by three other countries: Hungary, Poland and Serbia. All three nations share important similarities beyond the regular participation of their pronatalist schemes’ creators at the Budapest Demographic Summit.

First, all three countries were ruled by conservative and less-than-fully democratic governments at the time of the introduction of these policies. Of course, pronatalism is not the only topic on which Viktor Orbán’s Fidesz in Hungary, Aleksandar Vučić’s Serbian Progressive Party (SNS), and Jarosław Kaczyński’s Law and Justice (PiS) in Poland, which moved into opposition last autumn, are worth mentioning in the same sentence. From Budapest to Warsaw and Belgrade, pronatalism has coexisted with – and arguably strengthened – the popular appeal of these parties as the alleged protectors of their respective nations and core values. There is no better illustration of the uncontestable status that pronatalism has acquired in these countries than the fact that Poland’s new prime minister, Donald Tusk, has embraced and even vowed to expand the pronatalist policy he used to vehemently oppose.

Second, in all three cases, the pronatalist instrument of choice has been financial assistance for parents, which have mostly been designed to prioritize pronatalist goals over societal gain. On the one hand, pronatalism is not a zero-sum game: more cash can help current parents raise their children as much as it can encourage people to have (more) children. And the cash has definitely been flowing in spades. In Hungary, among other incentives, parents of three are exempt from paying income tax until the third child has turned 18 (as of 2019); parents of four are exempt for life (Orbán himself is a father of five). In Serbia and Poland, parents of four effectively receive an (additional) average monthly wage, which may not make a huge difference in Belgrade and Warsaw but often doubles the income of rural households.

Parents of one and two, however, don’t receive much more in Serbia and Hungary than they would elsewhere in Europe, even when accounting for the lower cost of living in the East. The Polish package is more balanced, even though it also carries some premiums past the second child. This can only be explained on pronatalist grounds: most people have one or two children regardless of policy, so the point of incentives is to encourage them to give birth to three or more. But this approach sacrifices social goals. Due to economies of scale, parents need less money for each additional child, as children in large families can share rooms and babysitters (or, in the case of large differences in age, babysit each other), pass down clothes and benefit from in-bulk food purchases. In Serbia, the timing of the support can also be problematized, as some of it is provided as a lump sum upon childbirth, possibly as a further nudge to parents. Even though it is usually older children who have more expensive consumption needs for anything from extracurriculars to clothing and entertainment.

Thus, despite the pronatalism of their governments, Hungarian and Serbian parents with one or two children – which will always make up the majority of the population regardless of policy – are poorer than they would be if they were childless. Policymakers offer them the opportunity to at least ‘break even’ but only if they have two additional children. Interestingly, however, the support becomes less generous – and in Serbia disappears altogether – from the fifth child onwards, possibly in an attempt to exclude Romani households, which face regular discrimination in both countries. Moreover, the tax-based nature of the Hungarian package serves an explicitly anti-egalitarian function, as the tax deduction, which is expressed as a share of income, translates into larger amounts for higher-earning families.

The fact that the packages provide the biggest boost to, say, well-off farmers with three or four children, while doing little to help low-income or even middle-income urban households meet the cost of living in large cities, speaks volumes about their political dimension. Our three countries of interest are no exception to the global realignment of voter loyalties away from class and towards more cultural concerns. The conservative governments in Hungary and Poland recognized a long time ago that an appeal to tradition is their strongest election winner: abortion restrictions (which have typically not been framed in pronatalist terms), for instance, gradually established themselves as one of Orbán and Kaczyński’s signature policies. As their voter base centres predominantly on the low-educated often from rural areas, who are more likely to have large families, pronatalism might have served as a key draw for this demographic. CEE pronatalist policymakers often like to take credit for having spotted the challenge of demographic change before ‘it is too late’, but the most cunning thing about their obsession with birth rate might have been their recognition of its enormous political value.

Cash alone won’t lead to more births

Even if CEE pronatalism serves a strong political function, its potential benefits in helping ageing populations mitigate their future public spending pressures and maintain their living standards remain valid. If pronatalism works, it might not matter if policymakers are embracing it for self-serving reasons. It shouldn’t be dismissed as missing the mark completely, especially since it has been around in its current form for what is still a rather short time. In Serbia, only since 2018. But its success is at best debatable.

The effectiveness of pronatalist policy is notoriously difficult to measure, as birth rates might change for reasons other than policy, including cultural trends and the age structure of a population. If a country happens to have many individuals of reproductive age at a given time, it might see a misleadingly high number of births. Similarly, if it is undergoing what is known as ‘fertility postponement’, or the usually gradual shift towards having children later in life, which European countries have indeed been experiencing over the past few decades, then births might seem misleadingly low in the short term.

It is reasonably safe to conclude, however, that pronatalism has not yet been a resounding success in any of the three CEE ‘poster countries’. Hungary’s birth rate, the highest of the three, is hovering around the EU average despite offering some of the strongest incentives on the continent. Poland saw births go up in the first few years since the introduction of its pronatalist policy in 2015 before declining again to currently one of the lowest levels in Europe: 1.3 children per woman. Serbia is, for now, seeing an increase but probably no more than a few hundred new births annually can be attributed to policy.

There are plenty of possible reasons for these underwhelming results. The prioritization of third and fourth children, while seemingly conducive to pronatalism, might not be the best way to boost birth rates in countries where most people don’t want to have more than two children. Moreover, in Hungary’s case, the focus on high-income individuals, not only through the tax-based nature of the support but also through the availability of housing top-ups, Only meaningful to those already close to being able to afford a home. might be counterproductive, as wealthier citizens tend to be less sensitive to policy nudges in the first place. Additionally, all three countries are characterized by some of the lowest levels of trust in government in Europe, indicating that citizens have little faith that the policies will be around long enough to be relevant to them, which might lead potential beneficiaries to exclude the packages from their family planning-related reasoning. Finally, the national-conservative and less-than-democratic climate in these countries might be deterring the more progressive layers of their populations from imagining a future at home, with or without policy.

Decoupling pronatalism from the likes of Orbán

Demographic change is a powerful thing: there is no developed country known to researchers, apart from perhaps Israel, whose context is for various reasons impossible to replicate, where population ageing and decline have been fully avoided. Yet, demographers also tend to agree that pronatalist policy is not pointless either: all family policies, including childcare, parental leave, and, yes, financial assistance, can do their small part in boosting birth rates, or more likely, in slowing their decline. Across CEE, governments have been providing more cash to parents, while at the same time curbing its pronatalist potential by failing to make childcare more accessible and affordable: the region continues to record some of the lowest enrolment rates, especially among children aged 0-3.

Serbian President Aleksandar Vucic once quipped that ‘if we don’t increase the number of children, we might as well “turn out the lights” behind us’. Inflated demographic alarmism aside, the real question might not be whether CEE can survive demographic change, but whether pronatalism can outlive the conservative agendas it is currently associated with. The case to watch right now is Poland: can progressives start embracing pronatalism if it no longer comes with abortion restrictions and ethnonationalist scaremongering? Demography, after all, is the science of hard numbers. The best thing policymakers and voters worrying about demographic change can do is to approach it free from ideological bias – be it from the Left or from the Right.

]]>

But the political situations in nation states and regional unions often bring the jurisdiction of borders into question. There are states determined to acquire more land. And those pushing to restrict legal entry. Forced migration, caused by environmental crises, war and poverty, has become a particularly keen topic for inhospitable hosts, focusing on both exclusion and expansionist solutions. The European Union’s bid to extend its border to third-country processing facilities for asylum seekers is a case in point.

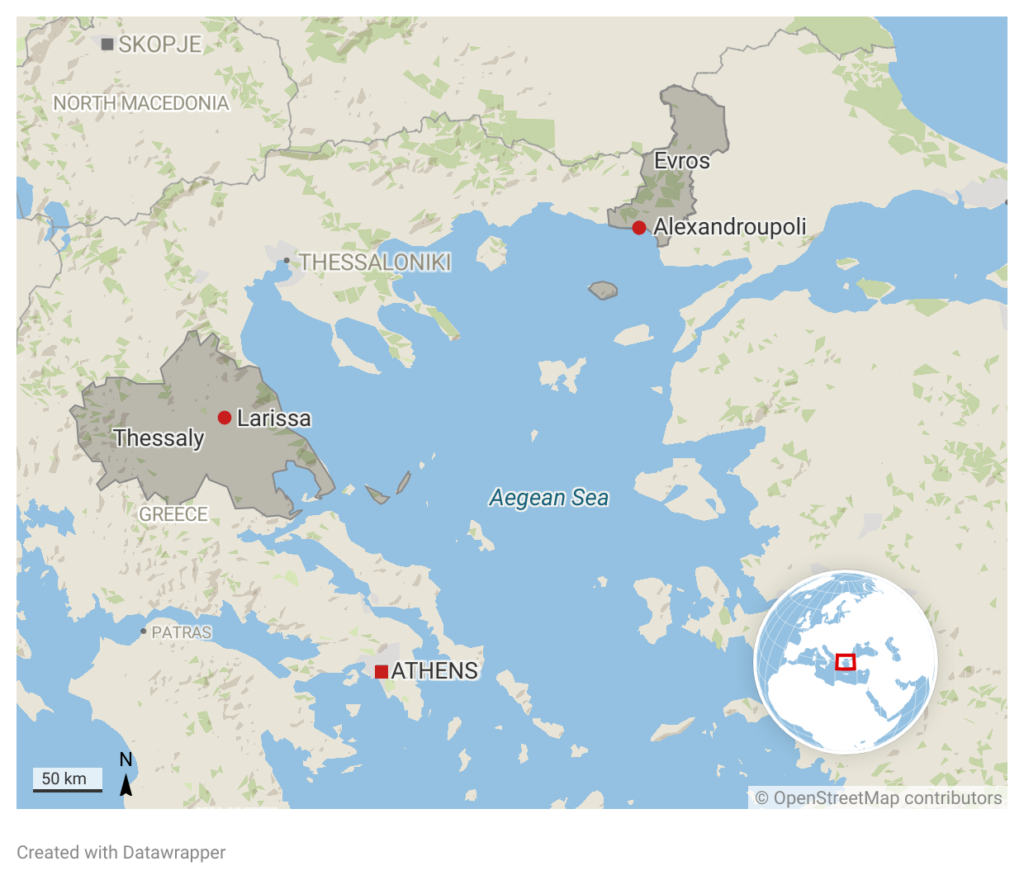

An interdisciplinary team of researchers at the University of Graz, collaborating with Eurozine on a new focal point, calls this phenomenon ‘Elastic Borders’: ‘Thinking of borders as elastic offers new avenues to understanding not only how state borders stretch and retract, but also how they create fields of stress and violations in the processes of extension and retraction.’ With contributions from the NOMIS foundation-funded research project and Eurozine partner journals, articles range from contemporary field work on contentious border practices in Greece, Spain and Tunisia to the legal and technological enactment of elastic borders.

Measuring the mobile body

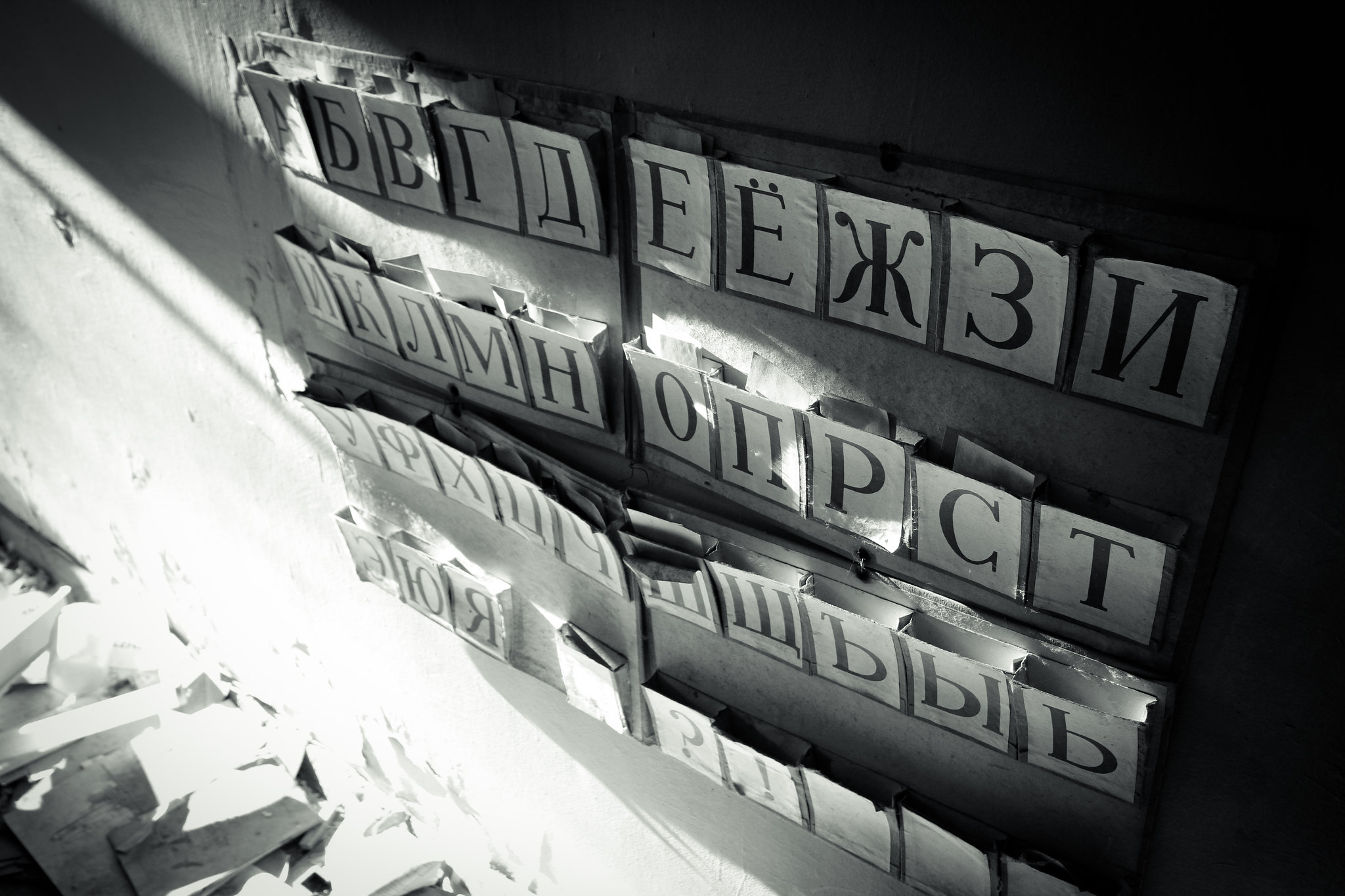

Laura Jung’s article on border and surveillance technologies takes us on a historical trawl. Her research draws parallels between late nineteenth-century criminology and contemporary data processing techniques. From painstakingly exact facial measurements to fingerprinting, the line between keeping a record of potential repeat offenders to profiling criminal types was easily crossed in the past. Enthusiasts enlisted scientific scrutiny for deviant ends. As Jung writes, criminal anthropologists ‘enumerated a list of so-called “stigmata” or physical regularities found in the body of the “born criminal”.’

Highlighting the crossover between criminology and eugenics, Jung references Frances Galton and his composite photographs of convicts. The process of attempting to identify markers of delinquency is itself now recognized as criminal.

And yet EU authorities utilizing biometric data processing to register migrants risk a similar transgression of human rights today. The Eurodac database, which records arrival points, fingerprints, photos and other forms of identification, may be espoused for its objectivity, supposedly eradicating human error and increasing ‘fairness’. But the notion that automated processes reduce bias is a simplistic argument. While machine learning may relieve the need for ongoing, incremental decisions, the system’s parameters will have been pre-set. Ethical biases, based on cultural prejudices and political allegiances, determine who will be targeted, how and when.

A tendency to criminalize in advance has resurfaced. And now that ‘the minimum age of migrants whose data can be stored has been lowered from fourteen to six years old,’ even the innocence of very small children is being corrupted by the system.

One way or another

Ongoing instability, due to conflict, environmental crises and economic hardship in parts of Africa, forces many to migrate. Chiara Pagano, focusing on Black migrants who make it to Tunisia’s borders, reports on state violence and informal trading. As a witness to this volatile situation, Pagano describes the disappearance of those attempting to make it to Europe. Once arrested, migrants are often brutally deported back across the border: ‘for over a month, Tunisian state authorities committed over 300 more migrants to their deaths; not readmitted, they were de facto trapped on the desert fringe between Tunisia and Libya under the scorching July sun’.

The European Commission, in paying the Tunisian government a €127 million first instalment in financial aid to combat what is deemed ‘irregularized migration’, is playing a pivotal role in this murderous scenario. ‘This move exemplified the EU’s active support of … the institutional, social and physical racialization of “sub-Saharan migrants” throughout their migratory path’, writes Pagano.

However, the strategic payment didn’t result in the closed border that the EU had hoped to leverage. And a subsequent transfer of 60 million euro was ‘dismissed as a disrespectful form of charity’. But the real reason for such a refusal seems to be based on a more pragmatic reality: ‘Keeping borders open is strategically more convenient to the Tunisian government than responding to EU blackmail, also due to the use that citizens and non-citizens on the Tunisian-Libyan frontier make of informal cross-border trade to navigate the country’s economic crisis.’ Pagano asks whether the EU’s failing cash for immobility plan is anything more than the legitimization of Tunisia’s authoritarian regime.

Tearing down fortress Europe

Writing for the Green European Journal, Aleksandra Savanović recognizes that safeguarding the dubious concept of a ‘European way of life’ has serious implications for migrants. Though indispensable for economic growth, new arrivals, who endure militarized border systems, face a future of privatized detention centres. Here, the EU also blatantly reveals its willingness to extend union borders when it suits ulterior motives: ‘member states … advocate for detention in 22 countries in the Balkans, Africa, Eastern Europe and West Asia … with the intention to eventually establish offshore processing facilities.’

Savanović asks whether a new focus on common goals could provide the necessary end to these dehumanizing practices: ‘What if, instead of investing in detention centres, we invest in elaborate social infrastructures that facilitate immigration by providing appropriate shelter, subsistence, and guidance?’ As with Jung, she proposes learning from a chequered past and repetitive present: ‘A place to start is turning away from utilitarian approaches that permit migration on the basis of need – like labour shortages or ageing populations – and, instead, taking a proactive, subject-centred view on migration futures.’

Chiara Pagano’s and Laura Jung’s research has been carried out during the ongoing project ‘Elastic Borders: Rethinking the Borders of the 21st Century’ based at the University of Graz.

]]>

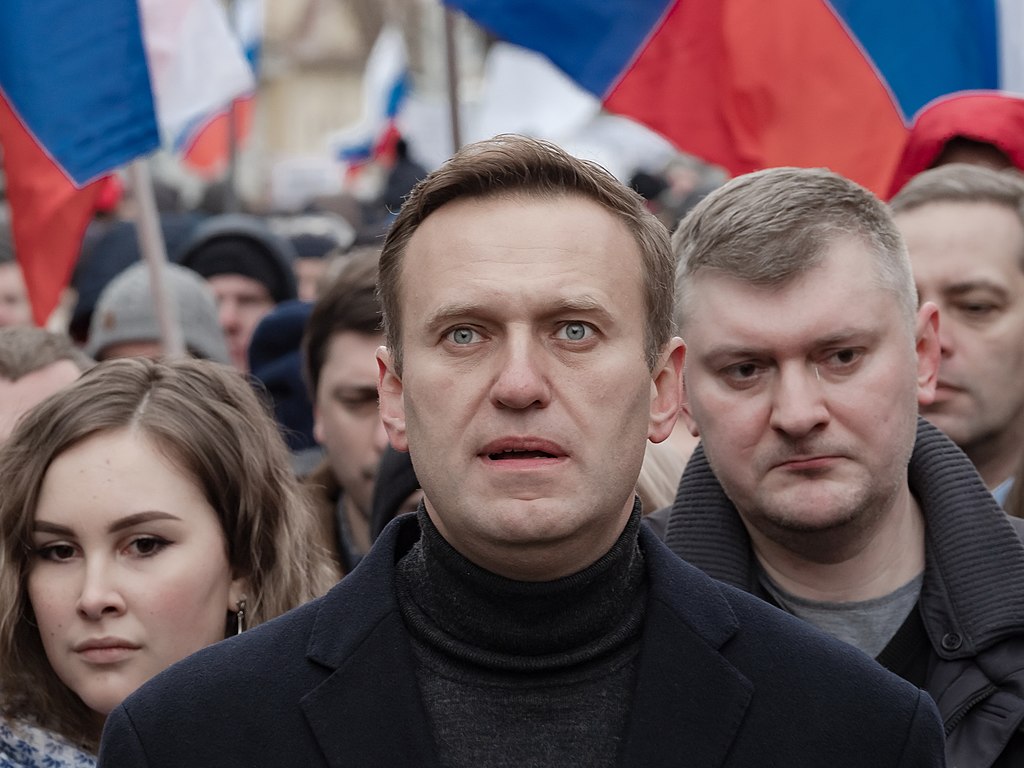

When intellectuals and politicians start talking obsessively about their country’s great ‘originality’, ‘special path’ and a ‘unique mission in the world’, it’s a sure sign they’re facing mounting problems in forging a modern democratic polity, civic nation and respectable international identity. Contemporary Russia is a case in point. Its new foreign policy doctrine, signed into law by President Vladimir Putin on 31 March 2023, is an astounding document declaring Russia’s civilizational uniqueness. Never before had a leader officially stated that Russia is a sui generis civilization. True, Catherine the Great, known for her occasional cockiness, was reported to have once said that ‘Russia itself is the universe and it doesn’t need anyone’. But the empress was quick to qualify her arrogant statement, adding that ‘Russia is a European country’. Yet Russian elites now appear ready to cut their country loose from its European moorings.

This radical ‘civilizational’ reorientation is of course the direct result of the war Russia has unleashed against Ukraine and the resolute and united response of Western democracies to the war. But Russian military aggression, driven by the Kremlin’s nationalist obsession, is in itself a manifestation of post-imperial Russia’s deep identity crisis. More the 30 years after the collapse of the Soviet Union, four key issues remain unresolved: Where do the boundaries of Russia’s political nation run? Are Russians capable of building a truly democratic polity or are they ‘historically’ destined to be ruled by authoritarian leaders? Is Russia a federation – as characterized in its Constitution – or is it a quasi-imperial entity? What is the ultimate objective of Russia’s historical development?

Kremlin leaders don’t give clear and straightforward answers to these questions. Instead, they obfuscate the real problems and set forth the idea of Russia as a ‘unique civilization’, while claiming that the West is in ‘terminal decline’ and ‘on its last legs’. The political implication of this rhetorical maneuver is not hard to fathom: the suggestion is that Russia need not follow ‘advanced’ Western nations as the latter are not ahead of Russia but, on the contrary, have lost their way and found themselves at a ‘historical dead end’.

Yet the notion of a special path (or Sonderweg), alongside the trope of the West’s decline, have a long intellectual pedigree. The Germans who coined the term, have managed to reinterpret their complex historical experience and turned Sonderweg into a research method: a historiographical tool, which has proved especially handy in the field of comparative studies. Most Russians, however, continue to view their historical experience as ‘unique’, eagerly embracing the notion of Sonderweg as the basis for self-identification and self-understanding.For a perceptive discussion of the Russian Sonderweg thesis, including in comparative perspective, see M. Velizhev, T. Atnashev, and A. Zorin, ‘Osoby put’: Ot ideologii k metodu, Novoe literaturnoe obozrenie, 2019; D. Travin, ‘Osoby put’ Rossii: Ot Dostoevskogo do Konchalovskogo, Izd. St. Peterburgskogo universiteta, 2018; A. Zaostrovtsev (ed.), Rossiia 1917-2017: Evropeiskaia modernizatsiia ili ‘osoby put’, Leont’evskii Tsentr, 2017; E. Pain (ed.), Ideologiia ‘osobogo puti’ v Rossii i Germanii: istoki, soderzhanie, posledstviia, Tri kvadrata, 2010.

Russia’s historic yardstick

Catherine the Great (detail), Vigilius Eriksen, 1760, Hermitage, St. Petersburg, Russia. Image via Wikimedia Commons

In his last letter to Pyotr Chaadaev from 19 October 1836, where Alexander Pushkin critiqued his friend’s idiosyncratic view of the Russian past, he also posed an intriguing question, wondering how a ‘future historian’ would see nineteenth-century Russia: Croyez-vous qu’il nous mettra hors l’Europe? (Do you think he will place us outside Europe?). A.S. Pushkin, Polnoe sobranie sochinenii, 6 vols, ed. M.A. Tsiavlovskii (Moscow: Khudozhestvennaia literatura, 1938) 4: 432. Pushkin, a consummate European who corresponded with Chaadaev exclusively in French, appeared to have been somewhat apprehensive about future historians characterizing Russia as a non-European country. Little did he know that statements advancing the thesis of Russia’s special path and proclaiming Europe ‘rotten’, ‘decrepit’ and even ‘dying’ would come from closer quarters.

Mortally wounded in a fateful duel in 1837, Pushkin didn’t witness the beginning of the grand debate on Russia’s identity, distinctive features of its historical development and its relation to Europe that was unleashed by the publication of Chaadaev’s first ‘philosophical letter’ – a debate that is still ongoing. It wasn’t a future historian but another nineteenth-century Russian poet Fyodor Tiutchev, four years Pushkin’s junior, who coined a paradigmatic formula of Russia’s samobytnost’ (originality): ‘No ordinary yardstick can span her greatness: She stands alone, unique’. F.I. Tiutchev, Polnoe sobranie sochinenii i pisem, 6 vols. (Moscow: IMLI, 2003) 2: 165

But how original were Tiutchev’s historiosophical musings about Russia’s originality? As a Russian diplomat, Tiutchev spent more than 20 years abroad, mostly at the Bavarian court in Munich, where he came under the strong influence of the German Romantic movement – a cultural phenomenon that was instrumental in Sonderweg’s emergence. During the wars of liberation against Napoleon, the German national consciousness and collective identity were formed in contrast to those of the French. Nineteenth-century historian Leopold von Ranke saw German history as unique: ‘each nation has a particular spirit, breathed into it by God, through which it is what it is and which its duty is to develop.’ L. Krieger, Ranke: The Meaning of History, University of Chicago Press, 1977. Moreover, it was deemed ‘the most important’, as Germany was thought of as ‘the mother’ of all other nations.

Ibid. Enthused about the founding of the new Reich in 1871 and proud of Imperial Germany’s economic power, many historians and political thinkers came to believe that a ‘positive German way’ existed. They readily contrasted strong, bureaucratic German state, reform from above, public service ethos and their famed Kultur with the Western notion of laissez-faire, with revolution, parliamentarianism, plutocracy and Zivilisation.

Not unlike their German counterparts, Tiutchev and other young Russian nobles (who would soon become known under the moniker of Slavophiles) saw a huge upsurge of Russian national feeling following victory over Napoleonic France. Twentieth-century philosopher Alexander Koyré aptly wrote, ‘national reaction was quickly turning into reactionary nationalism’. A. Koyré, La philosophie et le problème national en Russie au début du XIXe siècle, Champion, 1929. Against the backdrop of epic battles from 1812 to 1815, the representatives of early Russian Romanticism found the idea elaborated by their German intellectual gurus – Herder, Fichte and the brothers Schlegel – exceptionally appealing. They subscribed to the premise that German originality was based on a special type of culture, which couldn’t be conquered by brute force. The triumphant entry of Russian troops into Paris seemed to have upended the customary cultural hierarchy. The defeated French were cast as ‘barbarians’, while the Russians’ victory was attributed to their ‘national spirit’ rooted in the Russian language, historical traditions and Eastern Christian values.

When the grand debate, provoked by Chaadaev’s controversial publication, kicked off in the late 1830s, it zeroed in on two principal questions: Should Russia be compared with Western nations or is it following its own unique historical trajectory? And, are Russian ways superior or inferior to those in the West? Notably, both representatives of Russian ‘official nationalism’ and Russian Westernizers shared the view that Russia and Europe’s trajectories were identical. However, they sharply disagreed over who was in the lead: St. Petersburg imperial bureaucrats insisted on Russia’s superiority, while Westernizers argued that Russia was underdeveloped and lagging behind Europe. It was only the faithful disciples of German Romantic thinkers – Russian Slavophiles – who spoke in favor of Russian exceptionalism and produced what could be called the first interpretation of Russian Sonderweg.

The school of thought that exalted Russia’s divergence from Europe and the West, born from heated discussions from the 1840s to the 1850s, has remained central to the country’s intellectual life ever since. In the 1870s and 1880s, Neo-Slavophiles/Panslavists developed core Slavophile ideas of cultural oppositions: idealism vs. materialism, sobornost’ vs. individualism, selfless collective work vs. profit-obsessed capitalism, deep religious feeling vs. amoral cynicism. Nikolai Danilevskii’s theory of ‘cultural-historical types’ is a case in point. Eurasianists then delivered a complex theory on the vision of ‘Russia-Eurasia’ as a unique world unto itself in their writings of the 1920s and 1930s.

Two key aspects of Eurasianist political philosophy are especially influential on present-day Kremlin leaders. First, Eurasianists resolutely rejected a model of the nation-state, arguing that ‘Eurasia’ is a geopolitical space destined for imperial rule: the Russian/Eurasian empire was considered a ‘historical necessity’ based on a vision of the organic geographical, cultural and historical unity of the ‘imperial space’. Second, Eurasianists contended that Western-style parliamentary democracy was an alien institution, ‘culturally’ incompatible with Russian/Eurasian political folkways. They argued that the Eurasian political model was an ‘ideocracy’ – an authoritarian, one-party state ruled by a tightknit ideologically driven elite.

Eurasianists formulated their extravagant theories while keeping a close eye on events in the Soviet Union; there is no denying that Soviet policies and practices strongly influenced Eurasianist theorizing. But what, more specifically, of Soviet communism? Shouldn’t it also be analysed through the lens of the Russian Sonderweg paradigm? What is the historical significance of the Soviet period (1917-1991) if defined in relation to both European political practice and pre-revolutionary Russian political development?

Questioning Russia as exception

Soviet exceptionalism is a tricky case. On the one hand, as scholar Martin Malia perceptively notes, it ‘represents both maximal divergence from European norms and the great aberration in Russia’s own development.’ M. Malia, Russia under Western Eyes: From the bronze horseman to the Lenin mausoleum, Belknap Press, 1999, p. 12. Yet, while departing from European ways in terms of its practices and institutions, the Soviet Union was very much European ideologically. The combination of Marxist precepts and Russia’s poor socio-economic conditions ultimately shaped the Soviet experiment. Paradoxically, some Russian émigré thinkers suggested that the European far-left ideological foundations of the Soviet state might even force dyed-in-the-wool Russian conservative nationalists – the champions of ‘Holy Russia’ and detractors of Western publics’ ‘godless materialism’ – to reevaluate their anti-Western attitudes and embrace the ‘West’ they were living in. After the 1917 Revolution, poet Georgii Adamovich wittily noted, ‘the West and Russia seemed to have changed roles’: the renewed (communist) Russia ‘suddenly bypassed the West on the left’, abandoning its Christian vocation, while the West came to represent Christianity and Christian culture.

G. Adamovich, Kommentarii, Aleteia, 2000, pp. 184-185. ‘Very soon,’ wrote Adamovich sarcastically regarding Russian émigrés, ‘we, with our Russian inclination towards extremes, would probably hear about “West the God-bearer.”’

Ibid.

The official position within the Soviet Union, however, supposed that it represented a higher stage of universal civilization, much superior to that of the ‘capitalist West’. Even in the supposedly ideologically monolithic communist system, the old debate on Russia’s ‘uniqueness’ hadn’t died out. After a series of earlier iterations – Slavophiles vs. Westernizers, Populists vs. Marxists, Eurasianists vs. Europeanists – the notion resurrected in the form of a vibrant discussion between those who supported the idea of ‘building socialism in one country’ and the champions of ‘communist internationalism’. The discussion produced an intriguing paradox. Mikhail Pokrovskii, a leading Marxist historian, backed Stalin’s vision of ‘socialism with Soviet characteristics’, while Leon Trotsky called for the need to de-emphasize the idea of Russian historical peculiarity. Ironically, when Pokrovskii formulated his theory of merchant capitalism in the early 1910s, he was a staunch opponent of Russian exceptionalism and denied not only the existence of any significant Russian socio-economic samobytnost’ but also that of Russia’s backwardness vis-à-vis European nations. Trotsky, for his part, in his ‘German articles’ from 1908 and 1909, emerged as a strong supporter of Russian exceptionalism, emphasizing Russia’s divergence from Western ways.

The collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, heralding the end of Soviet exceptionalism, seemed to provide Russia with the opportunity to demystify its homegrown Sonderweg thesis and return – according to the phrase, popular with both rulers and citizens in the early 1990s – to ‘the family of civilized nations’. Even historian Richard Pipes, who placed a special premium on Russia’s ‘un-Western’ traits, appeared convinced that Sonderweg was at an end for Russia. ‘I think that now Russia has only one option left – turning West’, he argued in a short essay written in 2001 for the European Herald, a liberal, Moscow-based journal. By ‘West’ he intended a political community that comprises not only the US and the European Union but also such ‘Eastern’ nations as Japan, Taiwan and Singapore. ‘Nowadays it seems to me that for Russia a “special path” makes no sense.’ Dismissing the notion out of hand, he wrote in conclusion, ‘I don’t even know what it actually means.’ R. Pipes, ‘Osoby put’ dlia Rossii: chto konkretno eto znachit?’ Vestnik Evropy, No. 1, 2001, https://magazines.gorky.media/vestnik/2001/1

Russia’s cultural borrowing

And yet, 20 years on, the idea of ‘uniqueness’ and demonization of the ‘collective West’ are all the rage in Putin’s Russia. Why is this? The reason, I think, is twofold. First, unlike in 1960s and 1970s Germany, post-Soviet Russia didn’t see a vigorous nationwide debate among the country’s historians on the fundamental issues of Russia’s historical development. Some promising discussions that began during the twilight years of Mikhail Gorbachev’s perestroika didn’t bear much fruit and petered out in the chaotic era of the early 1990s. Second, as the Russian political regime has become increasingly authoritarian under Putin, the Kremlin has come to believe it is expedient to deploy the notion of Russian exceptionalism to buttress its position both domestically and internationally. Ukraine favoring ‘Europe’ has motivated Putin’s regime to rethink its international identity.

And yet, all the intellectual groundwork for deconstructing the idea of Russian uniqueness had already been laid by the time the Soviet Union collapsed. Several generations of pre-revolutionary Russian, émigré, Soviet, and international scholars had amply demonstrated that Russia is no more unique than any other country. Russia’s historical process, its social structure, state-society relations and political culture are indeed marked by sundry peculiarities, but these stem from Russia’s geopolitical position on the periphery of Europe: it sits on the eastern edges of the European cultural sphere and extends all the way to the border with China and the Pacific Ocean. Like many other countries, Russia borrowed its high culture from elsewhere, and did this twice: first, from Byzantine Constantinople; and then, in the late seventeenth to early eighteenth centuries, from the more advanced Western European cultural model. In both cases cultural norms, values and practices came from without. Russian cultural development should be understood as the process of mastering a ‘foreign’ experience.

Cultural borrowing does not mean, however, that Russian culture lacks a creative element. When Russia adopted certain aspects from another culture, the borrowed cultural models would find themselves in a completely different context, reshaping them into something new. These cultural phenomena would differ from both the original Western models and ‘old’ Russian cultural patterns. Perceptive Russian scholars like Boris Uspensky and Mikhail Gasparov note this paradox: it is precisely the orientation toward a ‘foreign’ culture that contributes to the originality of Russian culture. See: B.A. Uspensky and M.L. Gasparov, Russkaia intelligentsiia i zapadny intellektualizm: istoriia i tipologiia, B.A. Uspensky (ed.), O.G.I., 1999.

Yet such orientation contains significant tension in itself: the gravitation toward a ‘foreign’ culture is dialectically, and antithetically, linked with a desire to protect one’s own ‘authenticity’ and shield oneself from foreign cultural influences. The following dynamic ensues: the emerging inferiority complex gives rise to prickly nationalism, the search for a special path, mythologization of history, messianism and assertion of one’s special mission in the world. There is another paradox here that Uspensky also notes: it is precisely this nationalist backlash against a ‘foreign’ cultural tradition that is usually the least national and traditional. Craving for ‘authenticity’ and ‘national roots’ is most often the result of foreign influences – in the Russian case, the influences of Western culture that Russian intellectuals sought to repudiate. This is what puts early Slavophiles and German Romantics on the same page: the Germans felt they were culturally ‘colonized’ by the French and rebelled; the Russians borrowed the philosophical language of German Romanticism and applied it to their own situation. In both cases, this was a Sonderweg point of departure.

Unexclusive difference

But if we reject the existence of a sharp dividing line between ‘West’ and ‘East’ or between ‘Europe’ and ‘Russia’, acknowledging them as social constructs, what would a more suitable model explaining similarities and dissimilarities between national trajectories across the Eurasian continent be? The West-East ‘cultural gradient’, an understanding that there is a softer gradation and unity as one moves from Europe’s Atlantic coast eastwards all the way into the depth of Eurasia, is one option. See C. Evtuhov and S. Kotkin (eds.), The Cultural Gradient: The Transmission of Ideas in Europe, 1789-1991, Rowman and Littlefield Publishers, 2003. Pavel Miliukov introduced the idea in his multivolume Essays on the History of Russian Culture, which he thoroughly reworked in the 1920s and 1930s when in exile in Paris. Conceptually, the essays are based on two main theoretical principles. First, Russia’s historical evolution repeated the same stages through which other ‘cultured peoples of Europe’ had passed. Second, the process of this development was slower than in other parts of Europe: ‘not only in Western but also in Central Europe’. Miliukov’s bottom line was this: there was nothing particular or unique about Russia in this respect. ‘Peculiarity is not an exclusive feature of Russia. It shows up in the same manner in Europe itself, in a growing progression as we move from the Loire and the Seine to the Rhine, from the Rhine to the Vistula, from the Vistula to the Dnieper, and from the Dnieper to the Oka and the Volga’.

P. N. Miliukov, ‘Sotsiologicheskie osnovy russkogo istoricheskogo protsessa [1930]’, Rossiiskaia istoriia, No. 1, 2008, p. 160.

Miliukov’s ideas were further developed by émigré economist Alexander Gerschenkron, who positioned the European gradient at the basis of his highly influential model of industrial development. Gerschenkron’s thesis suggests ‘the farther east one goes in Europe the greater becomes the role of banks and of the state in fostering industrialization, a pattern complemented by the prevalence in backward areas of socialist or nationalist ideologies.’ M. Malia, Russia under Western Eyes, 440; Alexander Gerschenkron, Economic Backwardness in Historical Perspective, Belknap Press, 1962. Gerschenkron exerted a powerful intellectual influence on Richard Pipes’ lifelong opponent Martin Malia – a prominent Berkeley historian who perfected the concept of the West-East gradient. It became the essence of Malia’s exposition of the process of Russia’s social, intellectual and cultural development. ‘The farther east one goes,’ Malia contended, ‘the more absolute, centralized and bureaucratic governments become, the greater the pressure of the state on the individual, the more serious the obstacle to his independence, the more sweeping, general and abstract are ideologies of protest or of compensation’.

M. Malia, ‘Schiller and the Early Russian Left’, Harvard Slavic Studies IV, 1957, pp. 169-200. While Malia understood ‘Europe’ as a more or less coherent cultural sphere including Russia, he maintained that ‘Russia is the eastern extreme … she is the backward rear guard of Europe at the bottom of the slope of the West-East cultural gradient.’

M. Malia, The Soviet Tragedy: A History of Socialism in Russia, 1917-1991, The Free Press, 1994, p. 55. Another useful concept, as antidote to the discourse on backwardness, is Maria Todorova’s idea of ‘relative synchronicity within a longue durée development’. In analysing various European nationalisms within the unified structure of modernity, Todorova redefines the ‘East’ – Eastern Europe, the Balkans and Russia – as part of a common European space.

M. Todorova, ‘The Trap of Backwardness: Modernity, Temporality, and the Study of East European Nationalism’, Slavic Review, Vol 64, No. 1, 2005, pp. 140-164.

The European bloc

By the end of the 1980s, conceptualizing Russia within the pan-European context had become mainstream among Moscow governing elites. One of the key aspects of Mikhail Gorbachev’s ‘new thinking’ was the idea of a ‘common European home’. Boris Yeltsin talked of the need to ‘rejoin the European civilization’. Remarkably, as late as 2005, in his state of the nation address, Putin contended that Russia is ‘a major European power’, which for the past three centuries has been evolving and transforming itself ‘hand in hand’ and ‘together with other European nations’.